Claude Monet in the Countryside

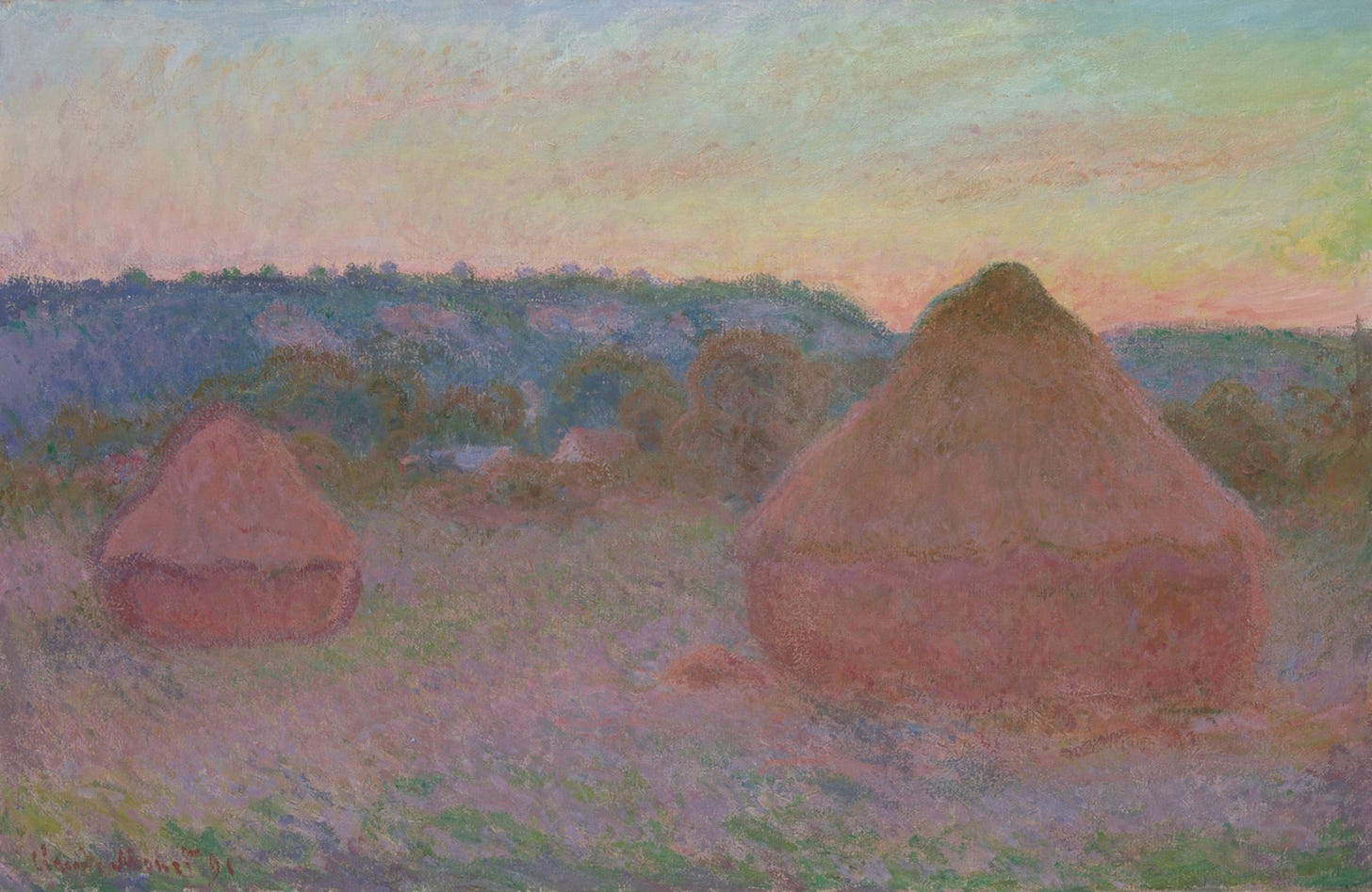

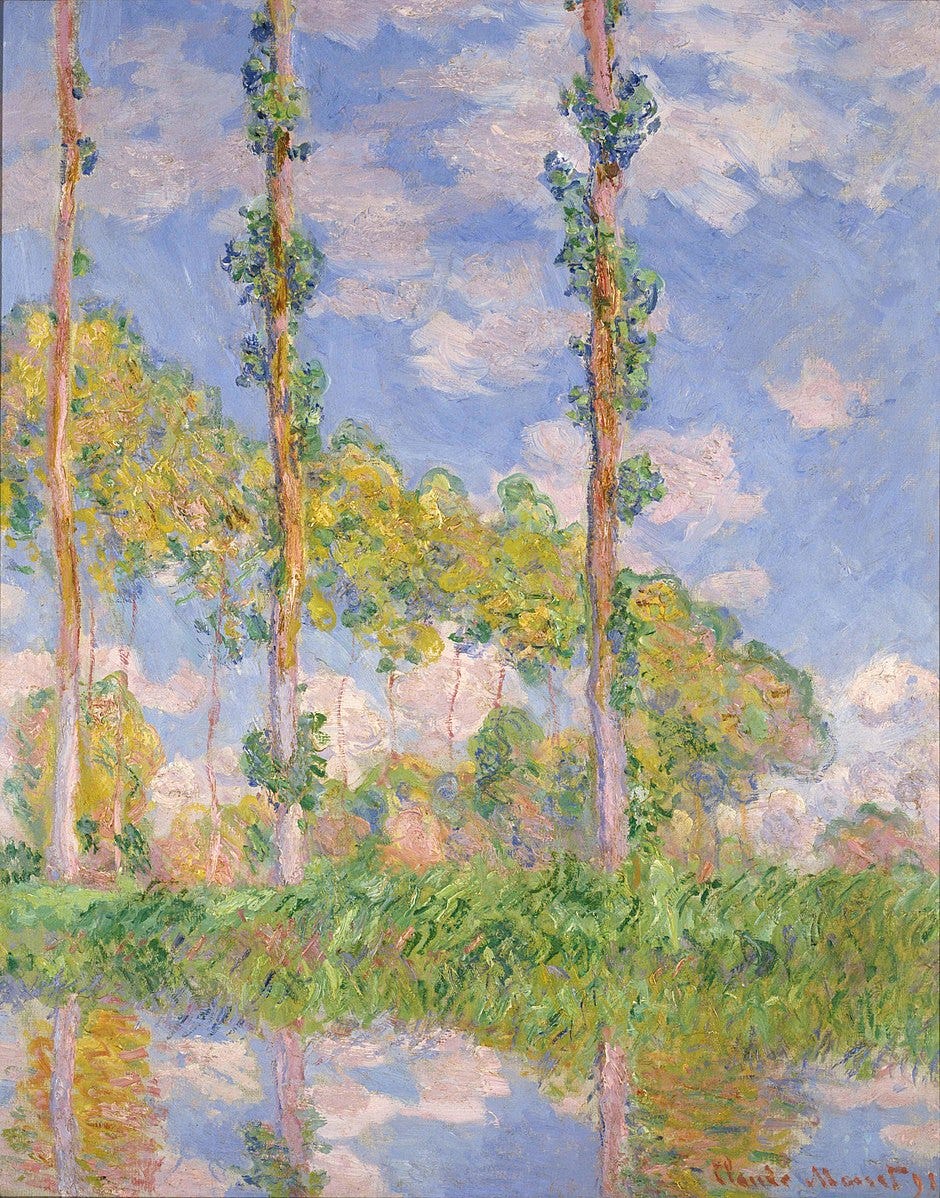

In "Claude Monet: The Art of the Series," we begin our visual journey with the Impressionist's studies of haystacks and poplar trees.

I’ve decided to pull this old series of patron essays from the archive, as most of you have not seen it. Below is the first in Claude Monet: The Art of the Series.

Claude Monet was just shy of fifty when he turned to the subject of haystacks.

Initially, it seemed a surprising choice for a man who, after thirty years of determination, had finally reached the brink of success. In 1886, longtime supporter and art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel had set sail for New York with numerous Impressionist canvases in tow—a decision that jump-started the movement’s international popularity. The following year, Monet, along with Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and countless others, participated in the Exposition Internationale at Georges Petit’s gallery in Paris. The Parisian bourgeoisie who once found the Impressionists shocking and horrid were changing their tune, and the artists now experienced greater ease in selling their work.1

Given this momentum, why would Monet turn to a subject that some of his contemporaries would criticize as unimaginative? Why was he so captivated by stacks of grain?

Monet’s eternal passion for the countryside motivated his decision to move with his family to Giverny in April 1883, just before the death of his ailing friend, Édouard Manet. While many of the original Impressionists were experimenting with different styles (such as Paul Cézanne’s later works, which would personify Post-Impressionism), Monet doubled down on his exploration of light and his efforts to capture fleeting visual impressions. While his earlier works sought to convey a more neutral record of what he saw, the artist was now introducing greater subjectivity in rendering his experience onto the canvas. As he explained, “For me, the subject is of secondary importance: I want to convey what is alive between me and the subject.”2

Beginning in the year 1888 but proceeding in earnest in 1890, Monet created his Haystacks series. This was not his first time using a series as a tool to exhibit seasonal shifts; earlier examples include Gare Saint-Lazare (1877) and The Pyramides at Port-Coton (1886). But Haystacks marks a transition into Monet’s mature style, one that endeavored to attain instantaneity. If light conditions changed, he would promptly stop and resume when similar conditions reappeared, “so as to get a true impression of a certain aspect of nature and not a composite picture.”3

This wasn’t without difficulty. Often, Monet was at the mercy of the weather, which only made his early struggles with rheumatism worse. He vented his frustration, in a characteristically expressive manner, when corresponding with his close friend Gustave Geffroy. On July 21st, 1890, Monet wrote:

I am very depressed and deeply disgusted with painting. It is really a continual torture. Don’t expect to see anything new; the little I was able to do is destroyed, scraped, or torn apart. You can’t imagine the dreadful weather we have had without interruption for two months. It’s enough to drive one raving mad, when one tries to capture the weather, the atmosphere, the surroundings.4

Throughout the seasons of 1890 and 1891, Monet painted stacks of grain in snow and sunshine, in early morning and afternoon. Using what otherwise may be considered simplistic subject matter, he is able to reveal subtle shifts in light and atmosphere. This is why museums that are lucky enough to have more than one piece from this series always display them together—the effect of seeing the stacks in a row allows the viewer to better appreciate the variation between each painting.

Monet pushed onward, as he always did. Within his garden at Giverny, he found an exciting source of inspiration among its bountiful blooms. (We will explore his Water Lilies in a future entry.) In 1891, he began working on another countryside series featuring the poplar trees that grew along the banks of the Epte. Poplar trees are deciduous trees that grow quickly and come in several varieties. Like his Haystacks, Monet’s Poplars series demonstrates the diversity of light and color in the French countryside as the land moves through different months.

If Monet had previously been on the edge of stardom, the Haystacks and Poplars launched him into the stratosphere. Within a few days of showcasing his Haystacks, all of them sold for prices ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 francs. (3,000 francs in 1890 comes out to roughly €20,000 to €25,000 today.) The advance from Durand-Ruel on his Poplars series would allow Monet to buy his property in Giverny, which he had previously been renting. Despite his success, Monet received criticism from some contemporaries, who felt that he was bowing to popular demand. Edgar Degas had once sniped, “[Monet’s art] was that of a skillful but not profound decorator.”5 To several critics, Monet’s Haystacks proved that Degas was right.

I have to disagree with Degas and the others on both points. First, it is clear from Monet’s letters during this period that these series were sincere artistic explorations, over which he agonized to such a degree that he destroyed numerous paintings. Monet was possibly his own most ferocious critic.

Second, I would argue that in his Haystacks and the series that would follow, Monet actually achieved the apotheosis of Impressionism as an aesthetic ideal. Despite his distaste toward philosophizing (oh, how artists hate to be categorized!), Monet accomplished the ultimate stylistic statement that the Impressionists carved out during their first exhibition in 1874. Here, we have an actual impression, or what he called “instantaneity,” which illustrates an observer’s subjective experience in nature. Unsurprisingly, Monet’s most recognizable works come from this later period, with his most famous being his Water Lilies.

Over the coming weeks, we will learn about some of the subjects that fascinated Monet, from the Gothic glory of Rouen Cathedral to the Houses of Parliament. Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) gave the Impressionist movement its name, and it seems fitting now to visit with the artist in the places he adored.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism: Fourth, Revised Edition (Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 547-548.

Christoph Heinrich, Monet (Taschen, 1994), 55-57.

Rewald, History of Impressionism, 562.

Linda Nochlin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism 1874-1904: Sources & Documents (Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966), 34.

Rewald, History of Impressionism, 564.

Nicole, thank you for the Footnotes and the 📍 "locations" of the art works 🌐 🖼️ 📚

Monet's pursuit of instantaneity in the Haystacks series is realy fascinating. The idea that he would stop and resume painting only when similar light conditions reappeared shows his dedication to capturing genuine impressons rather than composite images. Its interesting how critics like Degas dismissed his work as decorative when Monet was actually pushing Impresionism to its logical conclusion. The fact that he destroyed so many paintings out of dissatisfaction shows this wasn't just comercial pandering.