Edgar Degas: The Good, the Bad, and the Ballet

"The artist must live apart, and his private life should be unknown."

This essay is part of an ongoing series celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition, which debuted in Paris in 1874. If you’d like to read other essays on the history of Impressionism, you can do so here.

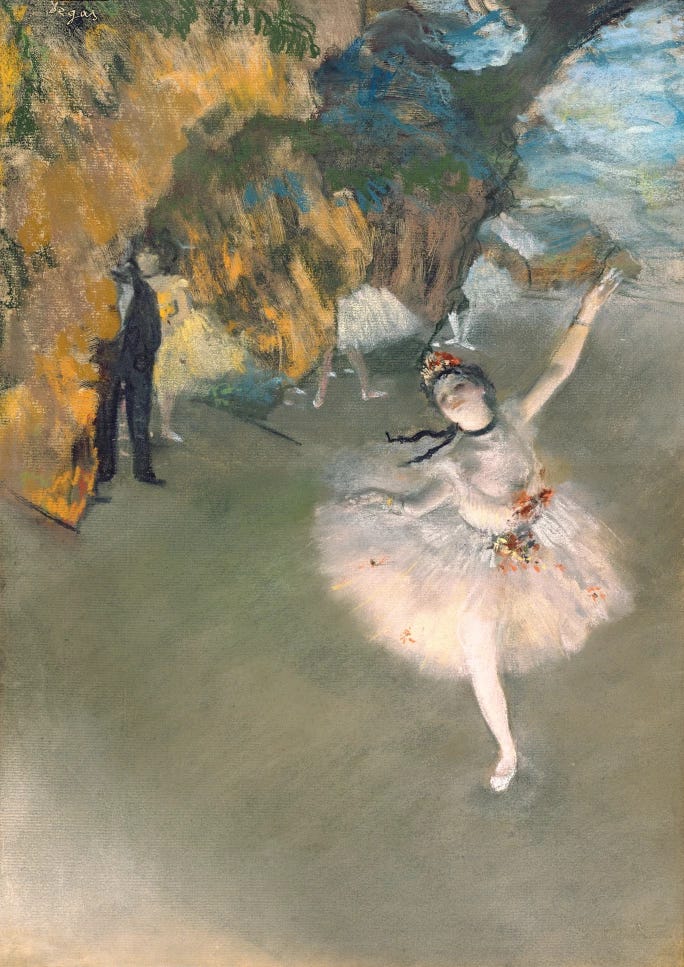

On the stage, a dream unfolded.

Young women in shimmering tulle and floral headpieces chasséd before a sea of spectators. Their movements were effortlessly synchronized to the orchestra music: every twirl, every leap transfixed their audience. The ballet was a testament to the sumptuous Belle-Époque. The Franco-Prussian War was over, the middle classes were on the rise, and France seemed poised to achieve something that few had seen coming since the 1770s: peace. Why shouldn’t they be joyful?

Backstage, a different reality emerged.

In our times, ballet is an activity reserved for the middle and upper classes. Being a dancer is prohibitively expensive. Parents have to pay for studio classes, replace worn-out shoes and tights, foot the bill for costumes and performances, and if their child is a competitive dancer, they must also supply fees for travel.

The dancers at the Paris Opera House came from radically different circumstances. Ballet was a job for working-class girls with limited options—no respectable young woman would dare appear onstage with her calves exposed for the world to see! To poor families, the ballet was a place to off-load a daughter and dispense of another mouth to feed.1

The ballet world was not without opportunity—if she played her cards right, a dancer could rise in the company’s ranks and become a household name. Women like Fanny Elssler and Marie Taglioni built their fortunes as ballerinas. But the industry was rife with exploitation. Dancers were expected to entertain abonnés, or wealthy male patrons of the Paris Opera. Their money came with the understanding that they would have access to scantily-clad dancers and the liberty to proposition them. In other words, being a ballet dancer was merely a step above common prostitution, a position of profound vulnerability. Allegedly, the dancers who spent more time with the abonnés were rewarded with better roles.

It is this dichotomy of beauty and exploitation that makes Edgar Degas’s paintings so fascinating, especially as it reflects the contradictions within Degas’s character. Our journey through the Impressionist movement has introduced us to a range of complicated personalities, but perhaps none so much as Degas.

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar de Gas was born in 1834 to a wealthy family. (He changed his name to the less-aristocratic Degas as an adult.) His father, Auguste de Gas, was a successful Neapolitan banker, and his mother Celestine came from an affluent Creole family in New Orleans, Louisiana. Degas lost his mother at the age of thirteen, and without getting too psychoanalytical, I do wonder if this contributed to his later troubles and resentment of women.

By the time Édouard Manet met Degas during a drawing session at the Louvre in 1863, the twenty-eight-year-old Degas had already grown exasperated with the Salon des Beaux-Arts. Degas’s formal arts education began eight years prior, in the studio of Louis Lamothe, where he gained an appreciation for the Old Masters and honed his drawing abilities. But like the other Impressionists, he chafed against the limits of academic art and the restrictive taste of the Salon judges.2

Manet introduced Degas to his circle of artists and bohemians; Degas soon found a home in the cafés of Montmartre and became friends with the painters who would become the Impressionists. Sure, he was an odd man: Degas was uneasy around women, and would often make disdainful remarks about marriage. “What would I want a wife for? Imagine having someone around who at the end of a grueling day in the studio said, ‘that’s a nice painting, dear.’” He could also be moody and withdrawn. “The artist must live apart, and his private life should be unknown.”3 Unlike the other Impressionists in our series, he hated the countryside and found little appeal in painting en plein air.

Degas was fascinated by artificial light in indoor spaces, and how this illuminated the contours of various figures. Settings such as the theater, cafés, and of course, the ballet offered ample opportunities to capture movement and intriguing shapes. (Horse-racing, another urban pastime, was also a favorite subject.)4 He painted scenes of ordinary life and working-class people, which would later scandalize the viewers of the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874. In this regard, his subject matter was the inverse of his friend Renoir’s work: Pierre-Auguste Renoir came from the working class and often painted the bourgeoisie. Degas came from the upper class and often painted the poor.

Degas was captivated by clothing; with the loose brushwork characteristic of the Impressionist style, fabric became ethereal in his hands. Despite the fact that he frequently exhibited with the Impressionists throughout his life, he disliked the group’s moniker (partially due to the lashing he received from critics after their first show). He called himself a Realist, though his style grew to be emblematic of Impressionism.

Laundresses, milliners, and ballet dancers filled his canvasses. When the writer Edmond de Goncourt visited Degas in his studio in 1874, Goncourt wrote in his journal that the artist “has fallen in love with the modern world”:

Degas places before our eyes laundresses and laundresses, while speaking their language and explaining to us technically the downward pressing and the circular strokes of iron, etc., etc. Next dancers file by… The painter shows you his pictures, from time to time adding to his explanation by mimicking a choreographic development, by imitating in the language of the dancers, one of their arabesques… What an original fellow, this Degas—sickly, hypochondriac, with such delicate eyes that he fears losing his sight, and for this very reason is especially sensitive and aware of the reverse character of things.5

Degas’s gradually declining eyesight only inflamed his misanthropic personality. Not only did he isolate himself further from his peers, but sadly, he grew virulently antisemitic towards the end of his life. This was catalyzed by the Dreyfus Affair, a gross miscarriage of justice that would divide all of Parisian society.

Captain Alfred Dreyfus was a French army officer who was falsely accused of sharing military secrets with the German Empire—the fact that Dreyfus was Jewish made him a perfect target during a time of intense antisemitism in France. Dreyfus was convicted of treason in 1894 and sent to a penal colony in French Guiana, where he was supposed to serve a life sentence. When further investigations revealed his innocence, and that the culprit was actually Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (a Christian), military officials tried to cover up their mistake.

It was Émile Zola (Paul Cézanne’s childhood friend) who wrote the 1898 op-ed that would catapult the case to the national conscience. His “J’Accuse...!” called out the French president, demanding that Captain Dreyfus be released from prison. For this, Zola was found guilty of libel, and he fled to England. Zola’s efforts did succeed in the end; the investigation was reopened and Dreyfus was found innocent. (He was reinstated in the army and went on to serve his country in World War I.)

Parisians split over Dreyfus’s innocence. The Impressionists were no exception: Camille Pissarro (who was Jewish), Claude Monet, and the American Mary Cassatt sided with Dreyfus. (Manet and Berthe Morisot had already died by the time Zola’s piece was published.) Cézanne believed Dreyfus was guilty, though he did not possess the extreme views of Degas and Renoir. The latter two cut ties with Pissarro, a kind man who offered nothing but generous goodwill and mentorship to younger artists. Degas went so far as refusing to acknowledge Pissarro when they passed each other on the street.6

Degas was a bundle of contradictions. In addition to his hatred of Jewish people, his contempt towards women (particularly older women) is well-established. Yet he maintained platonic friendships with certain women, including Morisot and Cassatt. I was surprised to learn that he joined Cassatt in holding a 1915 exhibition to raise money for the cause of women’s suffrage. However, his eyesight continued to decline, and he died two years later at the age of 83.

As a little girl, I was obsessed with ballet and all-things-pink. Unsurprisingly, Degas’s dancers were among my favorite paintings. When I began researching Degas’s life for this piece, I found myself continuously revisiting the ballerinas, this time because they seemed to perfectly embody the artist’s complex nature. He was capable of achieving extraordinary beauty despite the underlying ugliness of his beliefs. The ballet was a place of magic and fantasy, but backstage with the abonnés, it was the stuff of nightmares. Let us not forget that many of the dancers in these paintings were children.

Now, when I see the dancers, I am left wondering who they were: what were their dreams? Did any of them achieve the success of ballerinas like Elssler? What happened to these girls when they aged out of their grueling art form?

Because that is the other dimension to Degas’s ballet works that I missed as a kid—he was an artist painting other artists. Degas had his oils and pastels, but a dancer told stories with a perfect développé, or a gravity-defying grande jeté. With the stage as her canvas, every movement was the sweep of a brush.

Related from The Crossroads Gazette:

Julie Fiore, “The Sordid Truth behind Degas’s Ballet Dancers,” Artsy, October 1, 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-sordid-truth-degass-ballet-dancers.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Vintage, 2006), 33-34.

Roe, Private Lives, 35.

Ruth Schenkel, “Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Painting and Drawing,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dgsp/hd_dgsp.htm.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism: Fourth, Revised Edition (Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 278-279.

Rewald, History of Impressionism, 576.

This was a fascinating read and I followed up with Julie Fiore's piece. I knew nothing of the dark backstory of ballet at that time.

This may be a stretch but it reminds me a bit of comparing early professional sports and players of today. Professional athletes were blue collar , low pay part time employees who had to find real jobs to support themselves once the short seasons were over. They were chattel who were at the whim of their owners and once signed had no choice in leaving for another team. They could be bought and sold but they had no say in it. No where near the rock star wealthy players of today. Times change.

Brava! I also love the ballet and have a Degas keychain on my keys. Thank you for sharing this.