Paul Cézanne: The Outsider

"Surely this man has lived and lives a beautiful interior novel, and the demon of art dwells within him."

This essay is part of an ongoing series celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition, which debuted in Paris in 1874. If you’d like to read other essays on the history of Impressionism, you can do so here.

In August of 2023, the restoration team at Paul Cézanne’s family home, Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, made an exciting discovery. Hidden beneath a century of wallpaper and plaster was a previously-unknown mural by the artist. Dubbed Entrée du port, the work was created sometime between 1859 and 1864. Most of the mural has been destroyed by time, but one can make out the masts of ships, sails, and buildings in the port scene.

Cézanne’s father bought the property in Aix-en-Provence in 1859. Originally a milliner, Louis-Auguste Cézanne worked his way into the upper-middle class. Thanks to the success of his business, he bought the only bank in Aix, a decision that catapulted his family’s fortunes into the nouveau-riche. Paul Cézanne painted a series of murals in the grand salon of their new estate; unsatisfied with Entrée du port, he painted over it with Jeu de cache-cache in 1864. (When the Granel-Corsy family bought the estate in 1899, all of the known murals were transferred onto canvases and can now be found in museums around the world.)

This prodigious discovery of the unknown mural was well timed: to commemorate the completion of the estate’s restorations, Cézanne’s hometown of Aix will host a year-long celebration of the artist in 2025. “Cézanne 2025” closely coincides with the 150th anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition—this year, his paintings can also be found in special exhibits around the world honoring the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.

If Cézanne were alive today, he would have probably felt irritated to be grouped with the Impressionists. He never truly belonged.

Paul Cézanne arrived in Paris in 1861 at the age of twenty-two. Much to his father’s chagrin, he did not want to enter the family business and become a banker. Cézanne’s dream was to be an artist.

He enrolled in Suisse’s studio upon his arrival. It was there that he met Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, who visited the studio to meet “the strange Provençal” who had inspired much chatter from the other students.1 To say that Cézanne was a difficult character would be a vast understatement. He was notoriously rude, intense, and paranoid. Furthermore, Suisse’s pupils found his wobbly line drawings and lack of contouring bizarre. Pissarro, well known for his warmth and generosity, took the young artist under his wing.

Cézanne was originally inspired to move to Paris by his childhood friend, Émile Zola. The man who would one day become a famous author was currently working at the Librairie Hachette,2 and he worried about his troubled friend in Aix. Unfortunately, Cézanne’s demons followed him to Paris. As he wrote in a letter to his friend Joseph Huot:

I thought that by leaving Aix I should leave behind the boredom that pursues me. Actually I have done nothing but change my abode and the boredom has followed me. I have left my parents behind and my friends and some of my habits, that is all. And yet to think that I roam about almost the whole day. I have seen, it is naïve to say, the Louvre and the Luxembourg and Versailles. You know them, these boring things housed in these admirable monuments; it is astounding, startling, overwhelming… Do not think that I am becoming Parisian.3

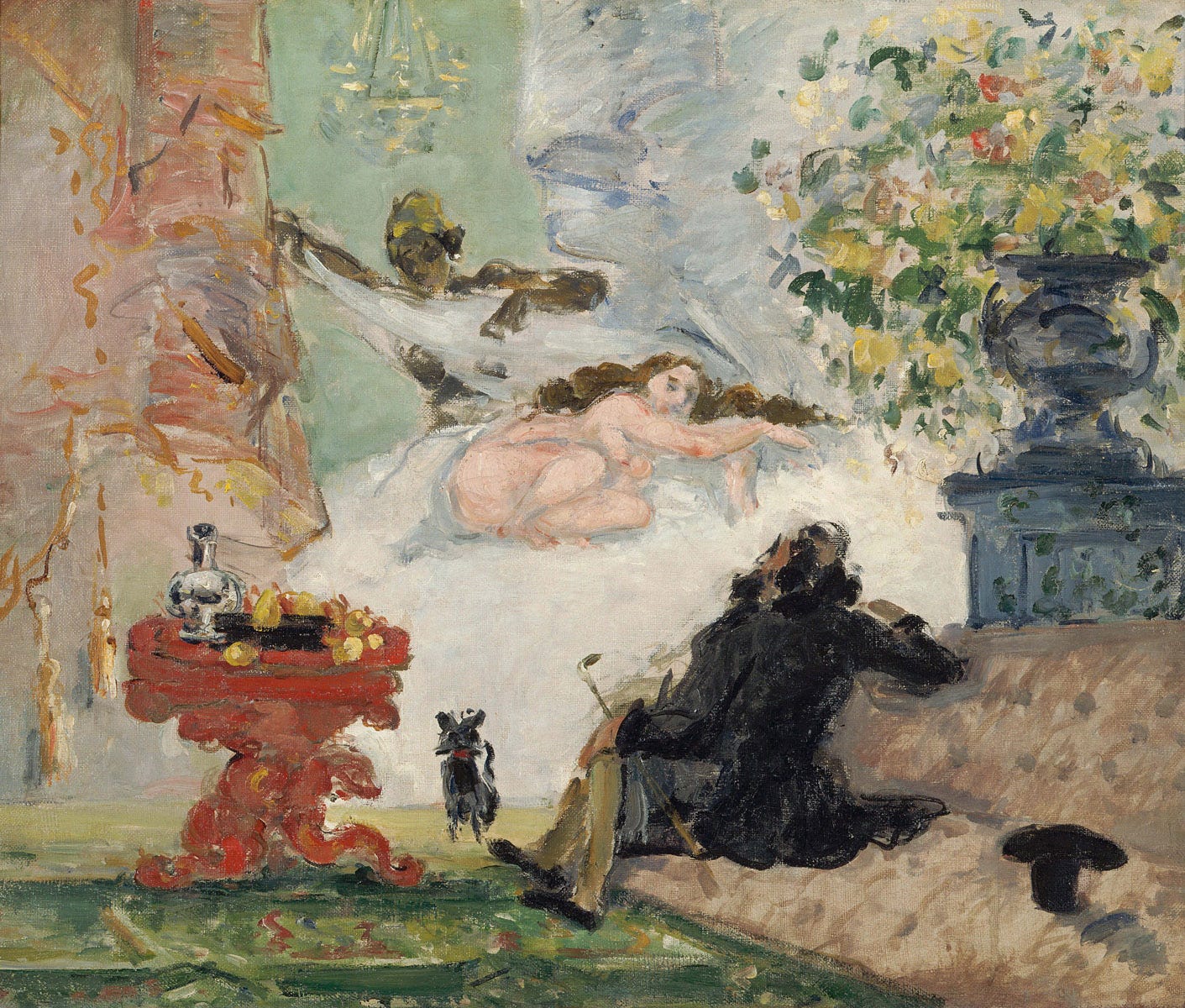

His depression worsened, partially due to the constant rejection he experienced from the Salon des Beaux-Arts. As with all of our Impressionists, Cézanne’s increasingly radical style made few inroads with the conservative artistic establishment. Cézanne’s earlier paintings often featured sharp contrasts in light and tone. His work in the 1860s was characterized by thick layers of paint, which he typically applied on the canvas with a palette knife.

Despite the fact that most art history textbooks would group Cézanne with the Post-Impressionists, he has been included in this series because he was one of the artists featured in the First Impressionist Exhibition. The failure of the exhibition crushed Cézanne, and he returned home to Aix for the first time in several years. There was just one problem: his mistress Hortense Fiquet was still in Paris with their two-year-old son, Paul Jr.

Cézanne tricked his father into continuing his allowance while he lived at the family estate—this was partly hastened by a glowing endorsement from the Director of the Aix Museum, who recognized Cézanne’s “genius.”4 With this allowance secured, Cézanne could return to Paris and support his secret family.

During the late 1870s and 1880s, his style began to diverge from the Impressionists. He grew especially interested in the structure of his subjects. His experimentation led to remarkable innovations in technique: instead of conveying depth through conventional perspective, he used subtle gradations of color.5

It was during this time that his family discovered the existence of Hortense and little Paul. The Cézannes were able to eventually reconcile (after all, the artist had also been born outside of marriage). Cézanne married Hortense in 1886, despite the fact that their relationship had long since broken down. The decision was made because Cézanne, poised to inherit a massive fortune from his father, needed to ensure that his beloved son would be a legitimate heir in the eyes of the law.

The 1880s also saw the breakdown of his friendship with Zola. The author had already achieved professional success, and Cézanne’s jealousy affected their relationship. In 1886, Zola published L’Œuvre, a novel about an emotionally-volatile painter whose revolutionary style is never recognized by the public, and in the end, he commits suicide. To add insult to injury, the artist’s friend in the story is a notable writer. Seeing the obvious parallels, Cézanne stopped speaking to Zola after the book’s publication—a rift that Cézanne would deeply regret upon Zola’s death.6

By the 1890s, Cézanne’s Impressionist period was truly in the rearview mirror. The work he produced in the last sixteen years of his life, which pioneered the use of overlapping swatches of paint to suggest geometric form and depth, paved the way for the Cubism and Abstract art of the 20th century.

His return to Provence in his final years gave him ample opportunity to capture the natural scenes he so loved, such as his series Montagne Sainte-Victoire. If you zoom in on the image below, you’ll see how he uses thick patches of paint to convey the shapes of trees and fields, the modest dwellings in the foreground, the ruggedness of the mountain in the distance. As he said in 1904, “Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.”7

The artist’s fortunes improved in the 1890s, thanks to an 1895 solo exhibition organized by art dealer Ambroise Vollard, which facilitated greater recognition in the press. However, his evolution beyond Impressionism meant that the public never truly “caught up” to his style during his lifetime. Like his mentor Pissarro, Cézanne remained just ahead of the curve. His relationship with Pissarro would weaken due to their diverging views on the Dreyfus Affair (a matter that we will discuss in greater depth when we turn to Degas and Renoir), but Cézanne always regarded himself as Pissarro’s pupil, stating that Pissarro “was a father for me.”

Sadly, Cézanne never gained true confidence in his abilities, telling his son in the final year of his life that while he could better understand how to paint from nature, “I still can’t do justice to the intensity unfolding before my senses.”8 Or, as the critic Gustav Geffroy aptly noted in Le Journal in 1894:

That Cézanne has not realized with the strength that he wanted the dream that invades him before the splendor of nature, that is certain, and that is his life and the life of many others. But it is also certain that his idea has revealed itself, and that the assemblage of his paintings would affirm a profound sensitivity, a rare unity of existence. Surely this man has lived and lives a beautiful interior novel, and the demon of art dwells within him.9

The demon of art dwells within him. I truly cannot think of a better way to express the anguish that haunted Cézanne. Perhaps this explains the heightened religiosity of his later years—the serenity he longed for was always just out of reach.

In the end, his influence would stretch far beyond his wildest dreams, as he inspired the likes of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp. Next year, admirers from around the world will visit his newly-restored home—the place to which he would retreat whenever the lingering storm clouds in his mind obscured his sight. It’s not surprising, then, that many his greatest works were produced in Provence. In the open air of the countryside, away from jeering critics and a fickle public, Cézanne’s brush could capture a fleeting vision of peace.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

Camille Pissarro Finds His Voice - “One must have only one master—nature; she is the one always to be consulted.” Read the full story here.

Berthe Morisot: the Great Lady of Impressionism - “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal and that’s all I would have asked for, for I know I’m worth as much as they.” Read the full story here.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Vintage, 2006), 15.

The Librairie Hachette would evolve into Hachette Livre, the third largest publishing group in the world.

Linda Nochlin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism 1874-1904: Sources & Documents (Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966), 83-84.

Sue Rose, Private Lives, 130-131.

“Paul Cézanne” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (DK, 2018), 368.

Sue Roe, Private Lives, 268.

“Paul Cézanne,” 369.

Sue Roe, Private Lives, 268.

Nochlin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 107.

Another real highlight in this series, Nicole. I love how you give such a brilliant insight into Cezanne's personality too. It's crazy to think that he could still feel as if his hands were never quite capturing what he saw or felt in his heart.

(Also really interested to read the story about the wall mural discovery too.)

Fantastic essay on a poet of the canvas.