Manet at the Café

"Never will he completely overcome the gaps in his temperament, but he has temperament, that is the important thing."

This essay is part of an ongoing series celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition, which debuted in Paris in 1874. If you’d like to read other essays on the history of Impressionism, you can do so here.

A group of painters meander through the cobbled streets of Montmartre as the sun sets over Paris. It’s 1863, and the city teems with new life. Baron Haussmann’s campaign to modernize its urban core has lured the growing middle classes to occupy what was once a chaotic, medieval city. Montmartre still lies on the outskirts, and it is here where artists, writers, and intellectuals gather.

The painters stop before the Café de Bade, the favorite of a man who has only recently shocked polite society with his painting, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863), at the Salon des Refusés. If the artists are lucky, they might find Monsieur Manet inside, surrounded by friends and admirers at one of the little round tables in the back of the boisterous room. All press is good press, and at the age of thirty-one, Manet has become a star.

Upon learning about his background, it’s not surprising to me that Édouard Manet felt at home in a café. In 19th-century Paris, cafés were bastions of intellectual life, where people could gather with friends to discuss art, politics, and literature. The café was also a place where Parisians of different social classes could occupy the same space. Manet came from an upper-class family and was never a true bohemian, but at the Café de Bade, he could befriend other artists and discuss his republican politics.

His republicanism may seem odd, given that his mother was the god-daughter of the King of Sweden, and his father was a Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Légion d’honneur, Judge of the First Instance of the Seine. I was also amused to learn that he grew up at 5, rue Bonaparte—directly across the street from the École des Beaux-Arts, with which the Impressionists had a quarrelsome relationship.1 Unlike his family, Manet rejected monarchy as a governing ideal; unlike the Impressionists, Manet respected the Salon des Beaux-Arts as an essential institution.

The café occupied a liminal space in Parisian society, and Manet, too, lived in the in-between. As his close friend, the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, once remarked, “Never will he completely overcome the gaps in his temperament, but he has temperament, that is the important thing.”2

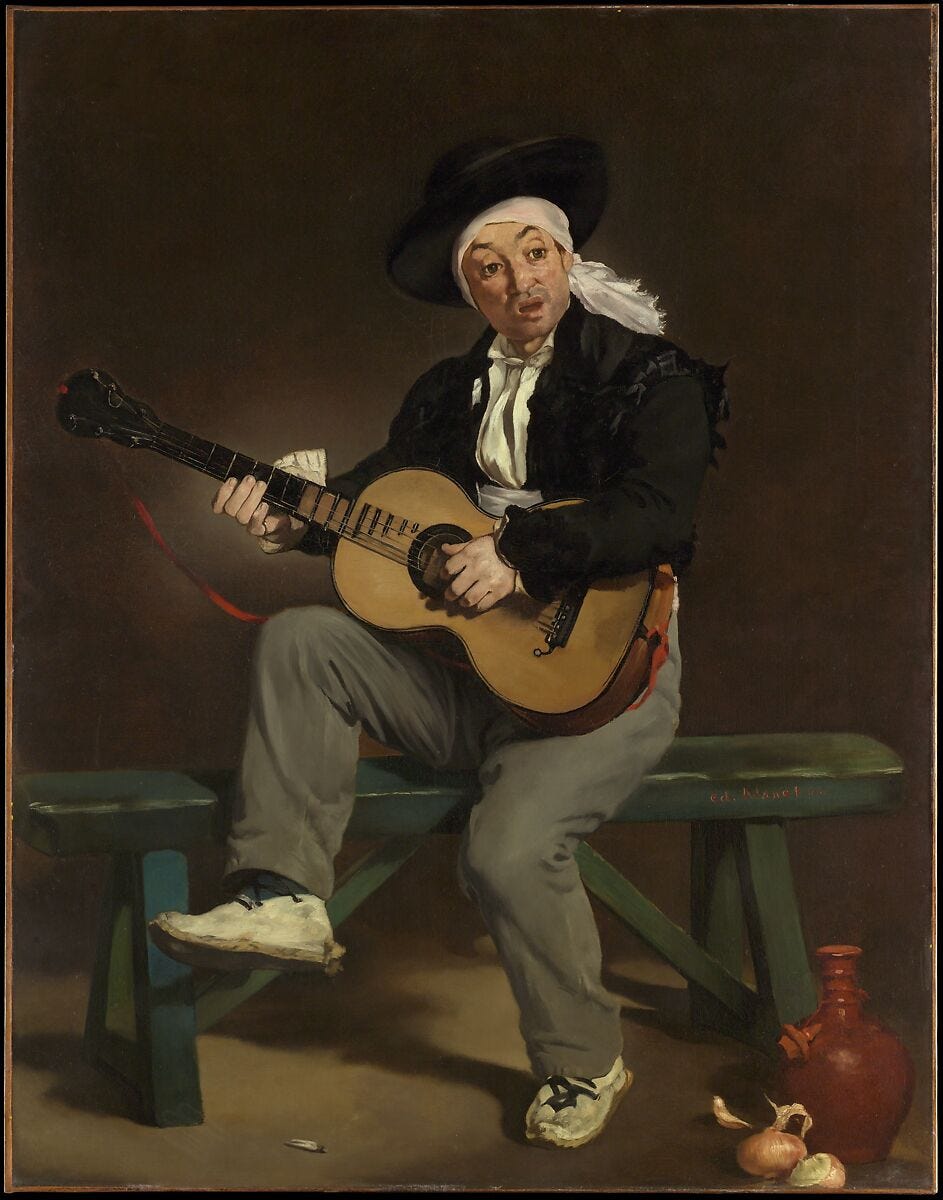

Manet rose to prominence during the 1860s, and the influence of the Realist movement is palpable in his early works. Paintings like The Absinthe Drinker (1859) and The Spanish Singer (1860) showcased moments from ordinary life. Manet resented the Salon’s predilection for history paintings, but he longed for official recognition and even managed to place a few works in its rarified halls. The Spanish Singer was one of them.

According to the French writer and literary critic Fernand Desnoyers, who saw The Spanish Singer at the Salon:

This canvas, which made so many painters’ eyes and mouths open wide, was signed by a new name, Manet. This Spanish musician was painted in a certain strange, new fashion, of which the young, astonished painters believed themselves alone to possess the secret, a kind of painting that stands between that called realistic and that called romantic.3

Manet would not be so lucky with Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, which he submitted for the 1863 Salon. This was the year that a record number of artists were rejected, leading to Napoleon III’s decision to allow a Salon des Refusés for the public to judge the art for themselves. As I wrote in the first essay in my Impressionists series, attendees were scandalized by the work. Audiences were only accustomed to seeing nudity within the context of mythological scenes; the realism and contemporary costuming in the painting hit too close to home. (Despite its realism, viewers can find early hints of an impressionistic landscape in the background.)

While Manet did not receive the institutional approval that he craved, the painting made him a celebrity. He would follow this up with Olympia (1863), which somehow made it past the Salon jury for the 1865 exhibition—this may be because its subject matter is modeled on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).

As John Berger famously wrote in Ways of Seeing:

If one compares [Manet’s] Olympia with Titian’s original, one sees a woman, cast in the traditional role, beginning to question that role, somewhat defiantly. The ideal was broken. But there was little replace it except the ‘realism’ of the prostitute—who became the quintessential woman of early avant-garde twentieth-century painting.4

The hypocrisy of Parisian bourgeois men was on full display. At the time, about 35,000 prostitutes worked in Paris, often for the hordes of middle-class men who were oh-so-shocked by a scene with which many of them were all too familiar.5 The cynical, defiant stare of the naked woman in the painting, modeled by French artist Victorine-Louise Meurent, transformed her from a thing to be admired to a person who sees the viewer.

To her right is a Black maid modeled by Laure, a woman whom Manet painted several times; tragically, we know very little about her. Laure posed for this painting just fifteen years after France had abolished slavery in its colonies. Perhaps the combination of a prostitute and a Black maid was too shocking for the sensibilities of Salon patrons.

Manet, as it turns out, was deeply hurt by the public’s reaction to Olympia. He fumed from the comfort of his table at the Café de Bade. To make matters worse, the Salon jury had admitted a painting by another artist with a horribly similar name: “Who is this Monet whose name sounds just like mine, and who is taking advantage of my notoriety?”6

Claude Monet, about eight years younger than Manet, deeply admired the elder artist’s work and certainly didn’t mind the comparisons. The two would eventually become friends, and Manet’s circle would expand to include other budding Impressionists (including his future sister-in-law, Berthe Morisot). While Manet didn’t think of himself as a revolutionary, he found himself in the perplexing position of spearheading a new movement.

If you’ve read my essay on the First Impressionist Exhibition, hosted in 1874 as a rebellion against the Salon, then you may recall that Manet refused to join. It didn’t matter: the public assumed that he was behind it. As Jules Claretie wrote in L’Indépendant on April 20th, 1874:

M. Manet is among those who assert that in painting one can, and indeed should, content oneself with the impression. We have seen more of the impressionists at Nadar’s. M. Monet — a more intransigent Manet, — Pissarro, Mlle Morisot etc., seem to have declared war on beauty.7

Manet’s fate was sealed. To this day, when one visits the Impressionist wing of any major museum, Manet’s work will be exhibited alongside Monet, Degas, and the others.

Never fear: Manet would eventually receive the accolades he desired. In 1881, the artist was awarded the Légion d’honneur. In his later years, he remained devoted to showcasing modern life, from painting the Monet family in their garden at Argenteuil (see above), to capturing scenes from his beloved cafés. He painted one of his last great works, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), while syphilis ravaged his health. Due to his declining strength, he needed a bar to be set up in his studio, with a bar maid modeling for him there.8

The figures appear blurry, painted from countless memories of evenings passed at Parisian cafés. As with many of his later works, it is much closer to Impressionism than Realism.

Édouard Manet died of syphilis the year after, at the age of 51. He would not live to see the Impressionists’ triumph in New York, and while he never exhibited with them, his death greatly impacted their cohesion as a group. Manet had a way of bringing people together. Holding court from his table in the back of a smoke-filled café, he was the quintessential embodiment of an evolving Parisian society. While his body of work may stand at the intersection of Realism and Impressionism, Manet earned his title as the Father of Modern Art, and the next time I visit my neighborhood café, I’ll toast him in remembrance.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

The (Eventual) Triumph of Claude Monet - “P.S. I was so upset yesterday that I made the blunder of throwing myself into the water. Fortunately, there were no bad results.” Read the full story here.

The Impressionist Exhibition, 150 Years Later - Today, the Impressionists are a ubiquitous presence in museums around the world. But the First Impressionist Exhibition, held in Paris in 1874, was met with uproar. Read the full story here.

Exclusives for Crossroads patrons:

Patron Podcast: Mermaids, Sirens, and Medieval Romance - Mesopotamian mythology, medieval bestiaries, and classic Disney movies: let’s explore how the mermaid transformed from the villain to the protagonist of her story. Listen to the latest episode here.

Last week’s Crossroads Roundup: Temple Complexes Discovered in Peru and Cyprus, a Fire at Rouen Cathedral, and France Gets a Cheese Museum - Our favorite stories on art, archaeology, folklore, and more from this past week. Read the full story here.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (London: Vintage, 2006), 29.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism: Fourth, Revised Edition (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 54.

Rewald, History of Impressionism, 52.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972), 63.

Roe, Private Lives, 40.

Roe, Private Lives, 41.

Roe, Private Lives, 128.

“Édouard Manet” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 343.

Cheers to you when you toast Manet. I found this very interesting.

Excellent survey of Manet’s works and impact. Thanks so much!