Mary Cassatt: The American Impressionist

"I have touched with a sense of art some people—they felt the love and the life. Can you offer me anything to compare to that joy for an artist?"

This essay is part of an ongoing series celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition, which debuted in Paris in 1874. If you’d like to read other essays on the history of Impressionism, you can do so here.

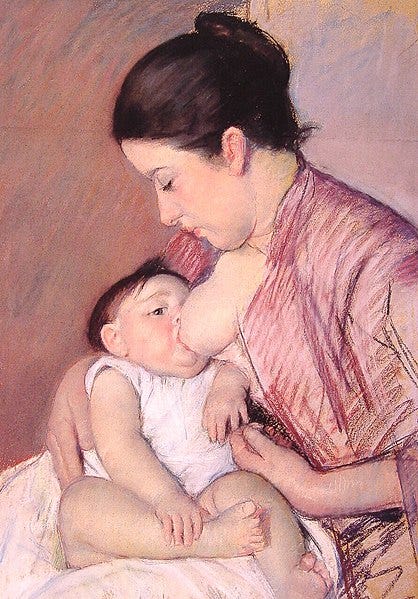

Early morning, the sound of little feet coming down the hallway rouses a young mother from her rest. Bleary eyed, desperate for a cup of tea, she nonetheless obliges her little one as the child reaches for her. A toddler cannot fathom that her mother is exhausted, that she really would rather sleep in. As soon as she is settled in her mother’s arms, the child’s needs are met for the moment, and her eyes are transfixed on something new in the distance. But the mother’s eyes are on the child, and one can only wonder what might be going through her mind.

In Mary Cassatt’s art, women are not passive models; the mother featured above in Breakfast in Bed (1897) is actively engaged in the scene. Her eyes reveal psychological depth and a rich inner life often missing from other 19th-century portraits by male artists. In other words, the women in Cassatt’s paintings are taken seriously.

As Impressionism grew in its reach and influence, artists overseas began to experiment with this new style. But only one American became a member of the original group—the last of the founders. That American was Mary Cassatt.

Cassatt was born in Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh) to a wealthy family of the Industrial era. Her father was a stockbroker and real estate agent, and her brother Aleck would become the Chairman of the American Railroad Company. The tall, loud, and stylish Mary showed promise in the arts at a young age; she studied in Philadelphia and Paris before embarking on a grand tour of Europe to learn from the Old Masters. After a brief return to Philadelphia during the Franco-Prussian War, she moved again to Paris in 1872 and made her Salon debut at the age of twenty-eight.1

But like the other Impressionists, Cassatt soon grew tired of the Salon’s rigidity. A trip to Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1874 would prove life-changing.

Accompanied by her friend Louisine Elder (who would later marry the head of the American Sugar Refining Company), Cassatt was captivated by a painting of ballerinas that defied the Salon’s norms. That artwork was Edgar Degas’s Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage (1874), one of the pieces shown at the infamous First Impressionist Exhibition. Cassatt persuaded Elder to buy the painting and take it back to New York, where it resides to this day in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Elder later reflected:

I scarcely knew how to appreciate it, or whether I liked it or not, for I believe it takes special brain cells to appreciate Degas. There was nothing the matter with Miss Cassatt’s brain cells, however, and she left me in no doubt as to the desirability of the purchase.

In fact, it was that same year when Degas would notice Cassatt’s art. She was showing again at the Salon, and Degas was taken with her painting of Tennyson’s Ida. “Here is someone who feels as I do,” he thought.2

Cassatt and Degas met several years later, and they became fast friends. They came from similar backgrounds, and they both emphasized the importance of draftsmanship in their work. All evidence points to their relationship being platonic; Degas, as we’ve explored, never wished to marry and, by all accounts, remained celibate throughout his life. (He seemed at once petrified and contemptuous towards women, and yet, his closest friends were women.) Though Cassatt deeply admired his work, she could clearly see the flaws in her friend’s personality. Cassatt once wrote to a friend:

Degas is a pessimist, and dissolves one so that you feel after being with him: “Oh, why try, since nothing can be done!” And this effect Gustave Moreau so felt that after a long friendship he said: “After all, I may be wrong, but I see things a certain way and must work that way, and I simply cannot see you, you upset and discourage me.”3

Nevertheless, Degas recognized the value of having another talented artist join the Impressionists, and he quickly introduced Cassatt to the group. For a woman of her social standing, exhibiting with radicals was a scandalous move. But Cassatt was now thirty-two years old, and she didn’t want to be just another “lady-painter” at the Salon. She was an artist, and the very best thing that can happen to any artist is realizing that one doesn’t have to care about others’ opinions.

Cassatt accepted Degas’s invitation “with delight. At last I could work in complete independence, without bothering about the eventual judgement of a jury.”4

In 1877, Cassatt’s family moved to Paris. Her father was retired, and her beloved sister Lydia was ill with Bright’s disease (deterioration of the kidneys); the Cassatts felt it would be prudent to keep the family together. Mary’s parents, particularly her father, had some reservations about their daughter’s increasingly bohemian lifestyle, and she would never marry nor have children. Nevertheless, they helped her to establish her own studio, with the understanding that it would have to support itself.5

Throughout this series, rejection has been a constant motif. The Impressionists battled scathing public criticism, such that by the time Degas decided to organize their fourth group exhibition in 1879, many members of the group were reluctant to participate—an early sign of cracks forming in their unity. He managed to persuade his friend Cassatt to join, as well as Pissarro and Monet, along with newcomers like Paul Gauguin. Much to everyone’s surprise, the show was a success. Attitudes were evolving, and the exhibition received over 16,000 paying visitors, with each painter making a profit of 439 francs.6

This event bonded Cassatt even more tightly to the group. Yet within just a few years, the Impressionists’ cohesion would fall apart.

All good things must come to an end, as we’ll see when I publish the final essay of this series at the end of the year. Before then, I wanted to share some thoughts on Cassatt’s art, and why her subject matter was so revolutionary.

All of the Impressionists broke the Salon’s norms by painting ordinary life and ordinary people. Both Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt took things a step further by elevating the lives of women; Cassatt in particular was preoccupied with capturing the feminine gaze on canvas. The women in her paintings are not passive figures—they are constantly examining and analyzing the world around them. A prominent example is her 1878 painting, In the Loge. The woman stares intently through her binoculars to scrutinize the performance onstage. Meanwhile, in the background of the composition, a man has his own binoculars trained on her—ogling her from a distance. If she is aware of his intrusion, she doesn’t reveal it. Her focus is firmly fixed upon the show.

Cassatt was a passionate feminist and suffragette, and her beliefs would put her at odds with members of her extended family. Her sister-in-law went as far as to organize a boycott one of Cassatt’s exhibitions held in support of women’s suffrage. (In retaliation, Cassatt sold all of her art that had been set aside for her heirs to ensure that her in-laws wouldn’t inherit them upon her death.) Cassatt had learned long ago to ignore the judgements of others.

Her later works were dominated by the subject that would make her famous: mothers and children. Intimate scenes, such as the tender moment captured in Breakfast in Bed, became a key source of inspiration.

It can be difficult for contemporary viewers to understand why these paintings were so revolutionary when to us, motherhood might seem commonplace. However, to a 19th-century viewer, private moments such as those depicted in The Child’s Bath (1893) or especially Maternité (1890) would have been shocking. In the world of fine art, mothers with their children could typically only be found in formal portraits, or in images of the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus. Through each of her works, Cassatt was proposing an argument that motherhood and the inner lives of women are important. They are worthy of high art.

Despite her strong reputation within the Impressionists’ circle, Mary Cassatt (like Berthe Morisot) was largely ignored by art historians until the late twentieth century. One hundred years after the birth of Impressionism, Cassatt is finally getting the credit that she deserves, with new exhibitions in Philadelphia and San Francisco, along with greater gallery space devoted to her art in museums around the world.

Cassatt once remarked, “I have touched with a sense of art some people—they felt the love and the life. Can you offer me anything to compare to that joy for an artist?” When I viewed Breakfast in Bed at the Huntington Library last month, that was exactly what I saw: love and life between a mother and child. Visual poetry, even—or perhaps, especially—in the quiet moments.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Vintage, 2006), 183-184.

Roe, Private Lives, 184.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism: Fourth, Revised Edition (Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 406.

Rewald, History of Impressionism, 408.

Roe, Private Lives, 191.

Roe, Private Lives, 203.

We just saw the exhibition in San Francisco. It was wonderful! Thanks for the deep dive and the context.

High time for Cassatt's time in the sun!