Claude Monet at Rouen Cathedral

In his next major series, the artist tackles a Gothic masterpiece.

This is the second essay in Claude Monet: The Art of the Series.

In 1895, a young Wassily Kandinsky was perusing an exhibit in Moscow when he came across a painting of haystacks. It was a strange artwork. The artist used feathery brushstrokes that gave what would otherwise be mundane stacks of grain a hazy character, as if the painter had glanced quickly in their direction while the sun was shining in his eyes.

Kandinsky was blown away. “Previously, I knew only realistic art,” he later reflected:

Suddenly, for the first time, I saw a “picture.” That it was a haystack, the catalogue informed me. I could not recognize it. This lack of recognition was distressing to me. I also felt that the painter had no right to paint so indistinctly. I had a muffled sense that the object was lacking in this picture, and was overcome with astonishment and perplexity… But what was absolutely clear to me was the unsuspected power, previously hidden from me, of the palette, which surpassed all my dreams. Painting took on a fabulous strength and splendor.1

Kandinsky would go on to become a major pioneer of abstract art in the twentieth century, but at the time, he was just one of many admirers of Monet’s later works. As we discussed in last week’s essay, the Haystacks series helped to make Claude Monet a global star, yet these works were also sincere explorations by an artist who wished to push Impressionism to new heights.

Most of Monet’s art is set outdoors; this is true even of his early works, before he became a leader of the Impressionist style. His next major series would focus on a new subject: closely “cropped” images (to use today’s photographic language) of an architectural masterpiece, in which the building’s structure is examined outside of the context of its setting.

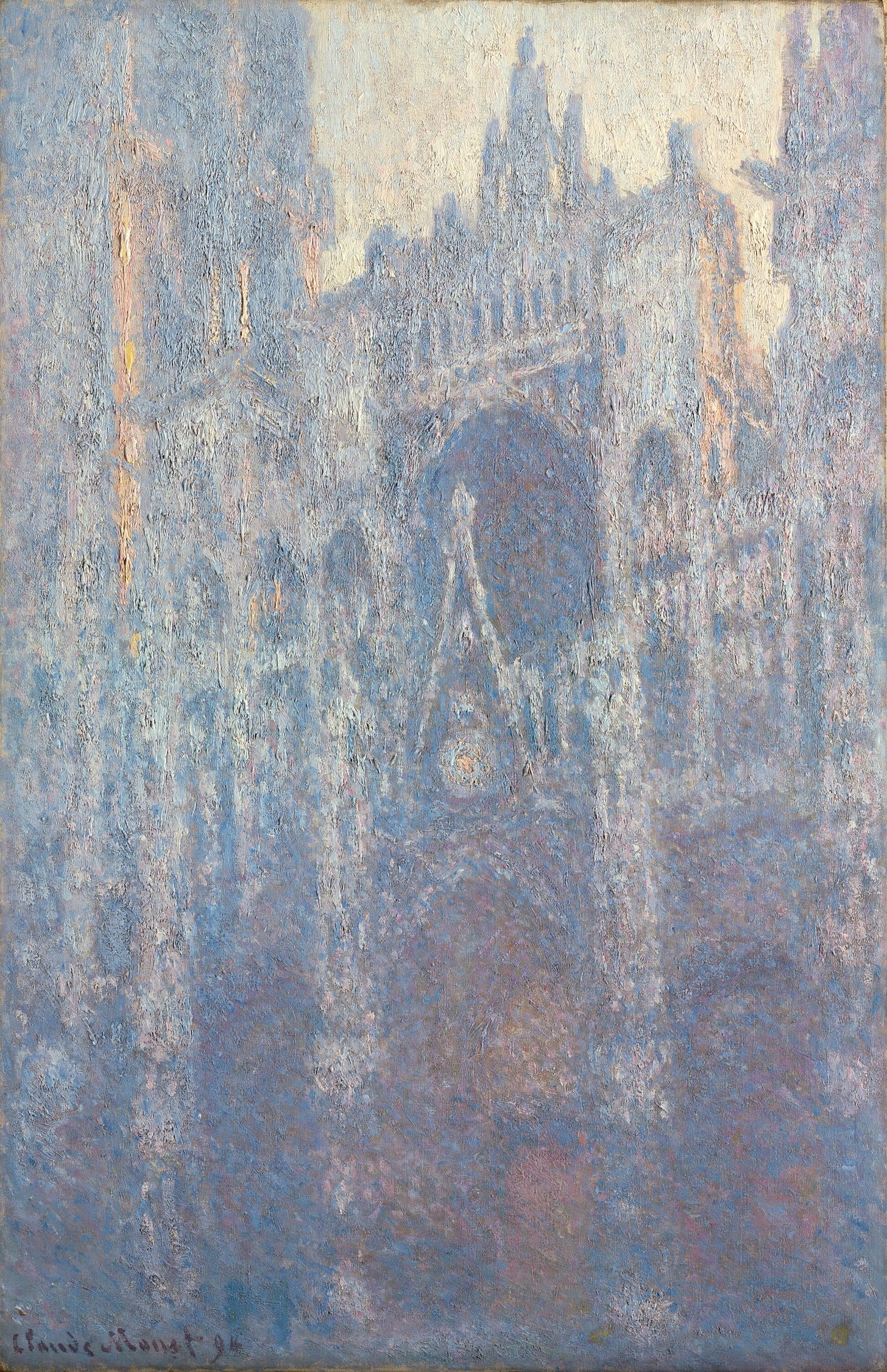

Rouen Cathedral sits in the center of Rouen, a city in Normandy that grew prosperous in the late Middle Ages. The towering spires of its Gothic cathedral are a testament to that wealth. Monet painted the cathedral’s exterior thirty times between 1892 and 1894. Beginning in February of 1892, the artist was able to gain a unique vantage point by renting a room directly across from the cathedral’s West façade; about two years into the project, Monet was forced to rent a different room, and the angle that he painted inevitably changed.2

As with his Haystacks and Poplars, the project of showcasing a subject in different seasons and light conditions continued. But the intricacies of Gothic architecture created new challenges (and possibilities).

One might think that Gothic architecture and Impressionism would make for an unlikely pair. Impressionism was all about looking forward, capturing modern life, and finding new techniques that painters could use to express themselves. However, these styles are united in an important area: both sought to capture and play with light.

Gothic architecture emerged in the mid-1100s, when church leaders decided they needed better methods to bring light into their buildings. The Romanesque churches of the 10th through 12th centuries adapted—and in some ways, improved upon—Roman building techniques to create arches and vaults. However, Romanesque architecture used less ornamentation than its Roman and Byzantine counterparts. In the words of 20th-century architect Harry Seidler, Romanesque buildings “[extended] the structural daring, with minimal visual elaboration.”3

Crucially, Romanesque churches had much smaller windows, and one of the earliest Gothic structures aimed to tackle this problem. The east end of the Abbey of St. Denis, north of Paris, was commissioned in the mid-12th century with explicit instructions to create a light-filled interior. Abbot Suger got exactly what he wanted: “The heart of the sanctuary glows in splendor… and the magnificent work shines, inundated with a new light.”4

This architectural transformation was possible thanks to the strategic use of flying buttresses and arches, which kept these massive buildings from collapsing even though their walls were overwhelmingly made of glass. Like an Impressionist canvas, stained glass windows painted the interior of Gothic churches in a kaleidoscope of color.

Painting Rouen Cathedral was something of a homecoming for Claude Monet. Monet grew up in Normandy, specifically in the port city of Le Havre: the subject of his 1872 painting Impression, Sunrise from which the Impressionist movement got its name. The Seine, another frequent subject in his art, connects Rouen and Le Havre with Paris. As Napoleon III would often muse, “Le Havre, Rouen, and Paris are a single city, in which the Seine is a winding road.”5

The Rouen series was an all-consuming endeavor. On March 30th, 1893, Monet wrote to the art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, “I am working as hard as I possibly can, and do not dream of doing anything except the cathedral. It is an immense task.”6 Each painting reveals the cathedral’s ornate carvings, columns, and spires in different lighting, and by removing Rouen from its setting and focusing on just its architectural details, Monet lends the cathedral a dream-like quality. Today, one can almost imagine it as the setting of a fantasy novel, a castle somewhere in the clouds. This is especially true of the cathedral’s façade in early morning, in which the pastel pinks and blues of sunrise offer the structure a fairytale glow.

For a 19th-century audience, this fantastical element likely would not have gone unnoticed. One of the architectural styles sweeping through Western Europe was the Gothic Revival, in which writers, artists, and architects found inspiration in the medieval world. This revival embraced a romanticized view of the period—a time of knights and dragons and chivalric romance—especially in the United Kingdom. In fact, Monet’s next major series would celebrate a masterpiece of the Gothic Revival in the UK: the Palace of Westminster.

In May of 1895, Durand-Ruel held an exhibition of twenty of the thirty Rouen paintings. It was an enormous success, and the pieces sold in quick succession. Monet’s friend, the future prime minister Georges Clemenceau, wanted the French government to buy the series so that the artworks would stay together. Monet declined.7 He was, after all, a child of Napoleon III’s France; in his lifetime, he had seen the country transform from the Second Empire to the Third Republic, with the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune appearing along the way. He possessed an instinctual distrust of government, and so the purchase never panned out.

Nevertheless, Monet had achieved his wildest dreams. After decades of striving, he was now an internationally-known artist. The mistake many artists of all stripes make is becoming complacent after finally seeing monetary success. Those who read my Impressionism series won’t be surprised to learn that he did not fall into that trap. Now was the time to seek new subjects and new locations. He traveled to Norway to visit his stepson, and he participated in motoring tours in Spain and Italy.

At the turn of the century, Monet stumbled upon another subject worthy of expanding into a series: views of the River Thames, and in particular, the Palace of Westminster. Next week, we will travel with Monet to Edwardian London and discover how the artist reckoned with light enveloped in fog.

Speaking of fairytales…

Recently on Fireside Fables: The Fairy Flag of Dunvegan

Last week’s episode of Fireside Fables explored the legend of the Fairy Flag of Dunvegan, a silk flag of mythical origins that hangs in Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism: Fourth, Revised Edition (Museum of Modern Art, 1973), 562-563.

Christoph Heinrich, Monet (Taschen, 1994), 56.

“Romanesque” in Architecture: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Kathryn Hennessy, Anita Kakar, and Angela Wilkes (DK, 2023), 100.

“Gothic,” Architecture, 162.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Vintage, 2006), 5.

Heinrich, Monet, 57.

Ibid.

Thank you! I so appreciate your attention to detail. And his work inspires me.

These two Gothic and Gothic Revival series are my favourites by this artist.

Apropos the fairy flag, have you visited Dunvegan? It's lochside setting is glorious, but the building itself is a solid lump and the largest pebbledash structure in Scotland!