Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is in the public domain. If you would like to follow along, you can read it for free here on Project Gutenberg’s website. Become a free or paid subscriber to ensure you never miss an episode:

You can also download the Substack app for free to listen to each chapter anywhere, anytime:

One of the central preoccupations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is growing older and becoming an adult. At various points in the narrative, Alice changes size, growing and shrinking to best suit whatever situation she finds herself in.

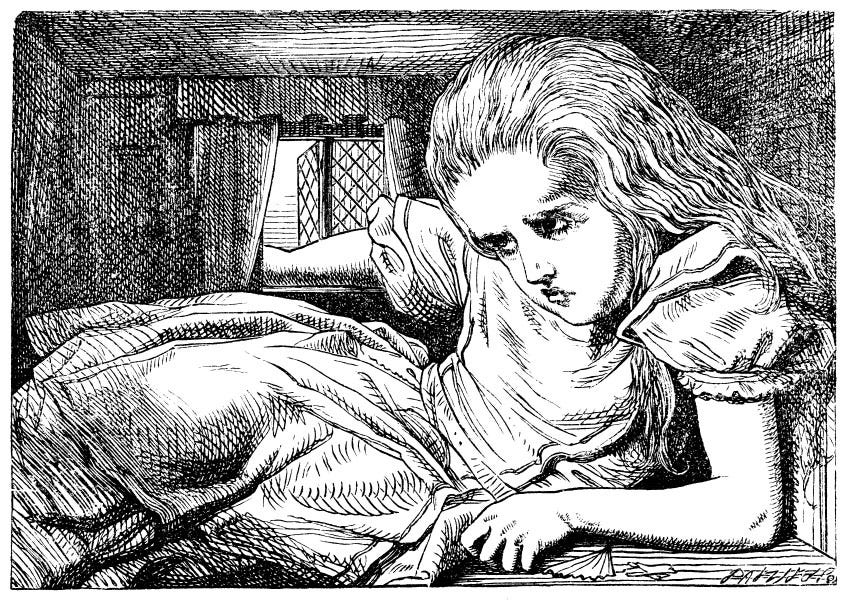

This week’s chapter showcases one of the more humorous instances of this shape-shifting—when the White Rabbit confuses Alice for his maid, and sends her to fetch his white kid gloves:

By this time she had found her way into a tidy little room with a table in the window, and on it (as she had hoped) a fan and two or three pairs of tiny white kid gloves: she took up the fan and a pair of the gloves, and was just going to leave the room, when her eye fell upon a little bottle that stood near the looking-glass. There was no label this time with the words “DRINK ME,” but nevertheless she uncorked it and put it to her lips. “I know something interesting is sure to happen,” she said to herself, “whenever I eat or drink anything; so I’ll just see what this bottle does. I do hope it’ll make me grow large again, for really I’m quite tired of being such a tiny little thing!”

The result is less than ideal.

What ensues is a hilarious chapter of anxious, anthropomorphic animals debating who will deal with the monster in the Rabbit’s house. (Should they burn down the building?)

To accompany this week’s entry of the Audio Book Club, I wanted to share some background information on Victorian childhood, and how important cultural developments can help us to better understand the text.

Childhood in Victorian England

Society’s understanding of childhood changed dramatically during Queen Victoria’s rule. Even prior to the Industrial Revolution, children were often treated as small adults, and unless they came from a family of means, they were forced to work.

This may sound exceptionally cruel, but keep in mind that for most of British history, the vast majority of people were farmers or craftspeople living in rural communities. Their lives included backbreaking manual labor and the bounty of their harvest was subject to the whims of nature (I get annoyed when modern urban professionals romanticize the very real hardships of “living off the land”)—but one benefit of this lifestyle was that people worked alongside their families and neighbors. When children were put to work on the farm, at the very least, they had their parents at their sides. They were not breathing toxic fumes or greatly endangering themselves.

Industrialization changed this, and for the children of the working class, this meant toiling indoors in dangerous factories for fourteen to sixteen hours per day. The business of farming ebbed and flowed with the seasons, with periods of rest during the winter. Factory work marched to the beat of a mechanistic future, in which every last drop of human productivity was ripe for extraction, and abuse. As the British public was forced to confront the stark reality of child labor in the industrial era, this ushered in a series of laws known as the Factory Acts, which gradually placed limits on the number of hours that children could work (though it wouldn’t be until the 1930s that school was made compulsory for all in the UK, and child labor for kids under 14 was banned entirely).1

By the time Lewis Carroll starting writing Alice, the Victorian conception of childhood was undergoing a transformation. Children were increasingly seen as a distinct class of people rather than small adults, and childhood was a time of innocence that needed to be cherished. Additionally, as the public moved away from literal interpretation of scripture, the biblical concept of “original sin” was replaced by the idea that children were a clean slate—born pure, until they became corrupted by the adult world.

Childhood in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

In her exploration of Carroll’s original manuscript, Alice’s Adventures Underground (the precursor to Wonderland), Melody Hansen of PRETEND IT EXISTS made this brilliant connection to British mining industries and the underground world Alice discovers:

Is the Under Ground, as seen in Carroll’s original title, an analogy for the mines? I’m beginning to understand Carroll’s rabbit hole as a hole into adult horrors and unjust perceptions, and Alice as a girl looking for the garden, looking for her way back to play and innocence.

I have yet to come across anyone who has made that connection to mining industries, but it makes sense—Alice literally tumbles into a hole in the earth, and finds herself in a world turned upside down.2

The character Alice is a member of the Victorian middle class—she is not an aristocrat, but she has the privilege of going to school (recall in Chapter 1, her preoccupation with forgetting her lessons while falling down the rabbit hole), and she does not have to work. Unsurprisingly, it was the middle- and upper-class children of Victorian Britain who enjoyed the greatest benefits of the “childhood revolution.”

Written in the 1860s, about 30 years after the first major influx of British child labor laws, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland negotiates between old and modern conceptions of childhood. Characters are often rude or dismissive of Alice, and in some cases, downright violent. (In this chapter, the White Rabbit and his employees nearly set her on fire.) Yet we see moments of Alice increasingly asserting herself and questioning the motives of those around her.

My favorite moment from this chapter showcases that reversal of authority, in which Alice, once bossed around by the White Rabbit, intimidates him and his servants thanks to her enlarged size:

“We must burn the house down!” said the Rabbit’s voice; and Alice called out as loud as she could, “If you do, I’ll set Dinah at you!”

There was a dead silence instantly, and Alice thought to herself, “I wonder what they will do next! If they had any sense, they’d take the roof off.” After a minute or two, they began moving about again, and Alice heard the Rabbit say, “A barrowful will do, to begin with.”

“A barrowful of what?” thought Alice; but she had not long to doubt, for the next moment a shower of little pebbles came rattling in at the window, and some of them hit her in the face. “I’ll put a stop to this,” she said to herself, and shouted out, “You’d better not do that again!” which produced another dead silence.

In the following chapter, we will meet a hookah-smoking Caterpillar, and Alice will further question her identity and her relationship to her ever-changing height. We will soon see how the existential questions posed by the text can be relatable to all of us, at any age, and how that aspect of the novel gives the narrative staying power beyond childhood.

Our theme song is “Fairy Chase” by Peter Cavallo. Licensing through Artlist.

Recent episodes of the Audio Book Club:

Audio Book Club: Chapter 3, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland - In which I promise to read more slowly, and we explore the work of Alice illustrator and political cartoonist Sir John Tenniel. Listen here.

Audio Book Club: Chapter 2, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland - How did Lewis Carroll come up with the idea for his beloved novel? That and more on this week's edition of the Audio Book Club, open to all! Listen here.

All episodes of the Audio Book Club can be found here.

For an excellent resource on all things Victorian, I would strongly recommend The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Culture, edited by Francis O’Gorman (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

A modern novel that plays with that concept of mines, labor, and an Underworld is Alix E. Harrow’s brilliant Southern Gothic, Starling House. One of my favorite books to come out last year!