Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is in the public domain. If you would like to follow along, you can read it for free here on Project Gutenberg’s website. Become a free or paid subscriber to ensure you never miss an episode:

You can also download the Substack app for free to listen to each chapter anywhere, anytime:

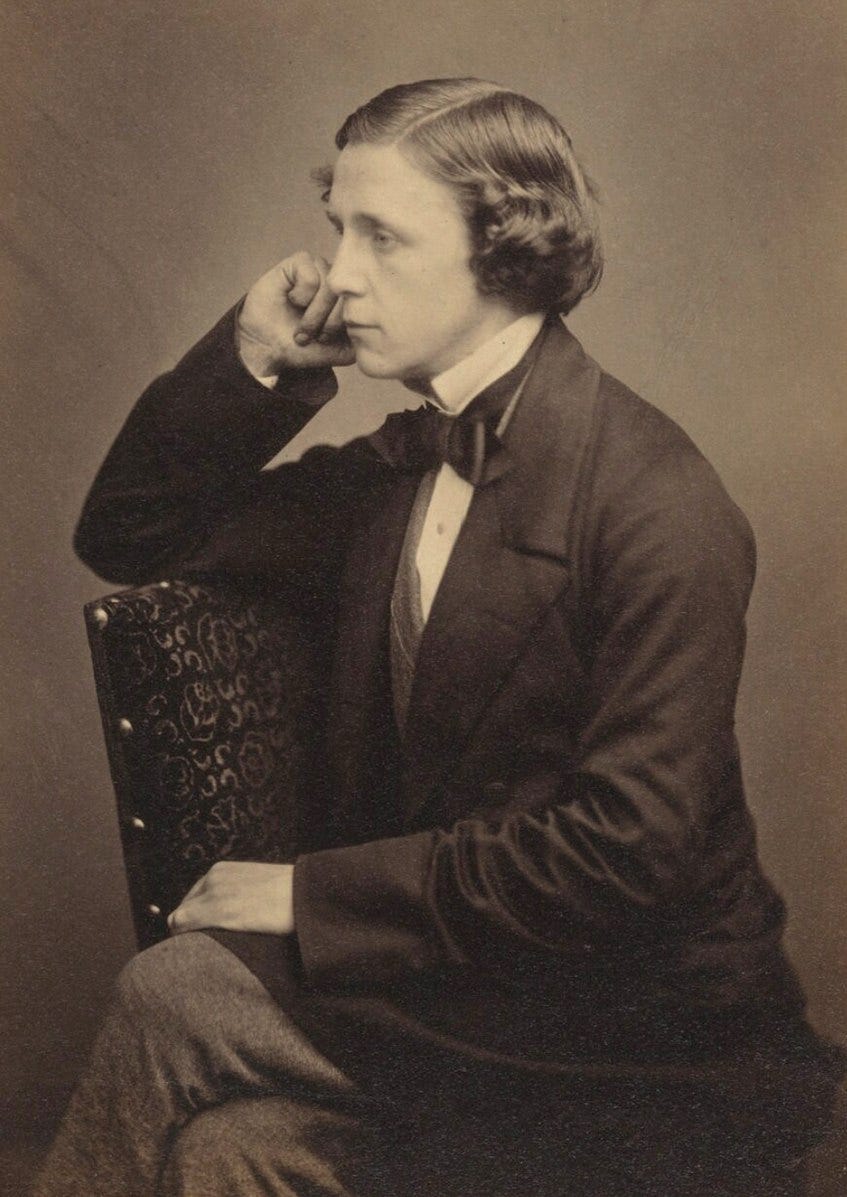

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was born in 1832 in Daresbury, England. He enjoyed a successful career as a mathematician, Anglican priest, and a photographer—but he is best known as the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871).

Here in the Audio Book Club, we will delve into Carroll’s work in greater detail in the coming weeks. But first, how did he come up with the idea for his beloved novel?

In 1856, Carroll met Henry Liddell, an educator and Anglican priest who became the Dean of Christ Church at Oxford University, where Carroll taught as a mathematician. Carroll quickly befriended Liddell’s wife (sparking later rumors of an affair), as well as Liddell’s son Harry and his three daughters: Lorina, Alice, and Edith. Carroll took the children under his wing, and would frequently take them out for picnics and boating excursions on the Thames.

It was during one of these boating excursions, on July 4th, 1862, that he invented a story about a little girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit hole and emerges in a magical land. The ten-year-old Alice Liddell loved the story so much that she insisted he write it down for her.

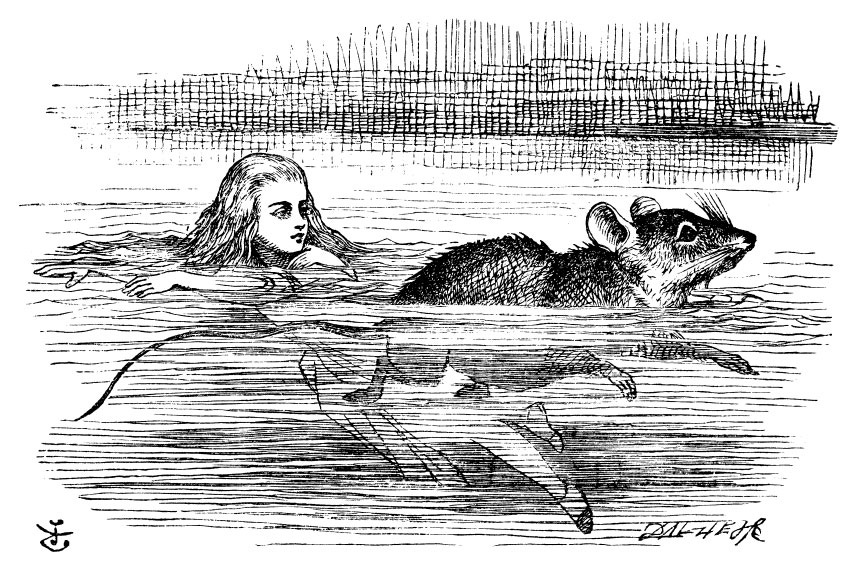

Carroll delayed on doing so, and he actually had an abrupt rift with Mr. and Mrs. Liddell in 1863 (more on that below). But the rift ended six months later, and in 1864, Carroll finally sent Alice a manuscript called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which became the basis of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Luckily, before sending Alice the manuscript, Carroll had shown it to Macmillan Publishers. With Macmillan, Carroll published an expanded version of his manuscript in 1865 with original illustrations by Sir John Tenniel.

The book was a resounding success, and Carroll would go on to publish a sequel called Through the Looking-Glass in 1871, cementing his status as an icon of Victorian children’s literature.

The elephant in the room…

Before we continue with our weekly explorations of Alice, I wanted to address the modern controversy surrounding Lewis Carroll and the nature of his relationship with Alice Liddell—some of which, as we’ll see, is colored by misunderstandings of Victorian social norms, as well as the decision by Carroll’s family to edit his diaries and remove references to his affairs with women, some of whom were married.

During the Victorian period, Carroll was regarded as a sort of “patron saint” of children. He was one of eleven siblings, and was used to being surrounded by play and making up stories for his family. Edward Wakeling, who annotated Carroll’s diaries, noted, “[Carroll] really enjoyed entertaining children, and they loved him in return.” He had many “child-friends,” as he called them, and it’s hard not to look uncomfortably upon that from our modern vantage point.

Here is the information that we do have:

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was an instant bestseller, completely selling out its original print run the year it was published and garnering prominent fans like Queen Victoria. No speculation regarding inappropriate relationships with children emerged during his life, and Carroll died in 1898 a national treasure.

Things changed in 1934, which was the year that Alice Liddell passed away at the age of eighty-two. A writer named A. M. E. Goldschmidt presented an essay at Oxford called “Alice in Wonderland Psycho-Analysed.” While Goldschmidt was not a psychoanalyst, he attempted to apply Freud’s methodologies to Carroll’s text by asserting that the story reveals suppressed sexual desires toward Alice. (He claimed that Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole is “a symbol for coitus.” Personally, I find that ridiculous.)

The essay slowly gained traction in academic circles; as I mentioned, Liddell had by now passed away and therefore could not weigh in. By the 1940s, the idea that Alice contained dark, hidden meanings persisted.

Then, in 1945, Florence Becker Lennon published a biography of Carroll called Victoria Through the Looking Glass, in which she asserts that he had inappropriate feelings toward young girls and speculates that he had attempted to propose to Alice (and that this led to his rift with her parents). Before Alice Liddell died, Lennon interviewed her older sister, Lorina (“Ina”).

Ina wrote a letter to her sister after the interview and expressed her regret for speaking with Lennon: “I said his manner became too affectionate to you as you grew older and that mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him, so he ceased coming to visit us again.” However, Ina doesn’t elaborate on why she regretted her statement to Lennon.

As biographer and journalist Jenny Woolf notes:

Lennon acknowledged that she wrote without the benefit of Dodgson’s diaries, which were published in abridged form in 1954 and in full, with Wakeling’s annotations, beginning in 1993. But even they are an imperfect source. Four of the 13 volumes are missing—as are the pages covering late June 1863, when his break with the Liddells occurred. A Dodgson descendant apparently cut them out after the writer died.

What could have been in those missing pages?

One clue comes from what is now known as the “Cut pages in diary” document. Earlier, I mentioned that after his death, Lewis Carroll’s family edited his diaries to remove references to his relationships (and romantic affairs) with grown women. These omissions weren’t brought to light until the late 20th century—and without these entries, it’s understandable why earlier scholars would gain the perception that Carroll was only interested in spending time with children. It also sheds light on Victorian attitudes regarding friendships between adults and children; Carroll’s family didn’t feel the need to cut any of those entries, but they clearly wished to conceal his love affairs and friendships with adult women.

In the “Cut pages in dairy” document, someone (allegedly, Carroll’s nephew) kept notes about the contents of a few of Carroll’s diary pages that his family destroyed. Regarding the missing pages from 1863, during the weeks when the Liddell-Carroll rift occurred, the author writes:

L.C. learns from Mrs. Liddell that he is supposed to be using the children as a means of paying court to the governess—he is also supposed by some to be courting Ina.

In other words, rumors swirled that Carroll was spending time with the Liddell kids to conduct an affair with their governess, and that other rumors circulated about his courting Alice’s older sister, Ina. The author of the note does not say whether either of these rumors were true, and some scholars have theorized that Ina’s comments to Lennon were intended to protect her reputation. Others have even suggested that Carroll was having an affair with Mrs. Liddell. I’m not going to speculate here, as there isn’t enough evidence in either case.

Another element of Victorian culture that could understandably be misconstrued today relates to their practice of photographing small children unclothed. We’ll discuss the nuances of Victorian childhood in later entries, but one thing to know is that the Victorians regarded childhood as a time of perfect innocence—something pure and fleeting that needed to be captured. Photographers like Carroll and Julia Margaret Cameron frequently photographed children, and unclothed images were regarded as symbols of Edenic purity. (It wasn’t uncommon for affluent families to commission these portraits.)

For obvious reasons, I will not be sharing those images here, and as a person of my time, I do find it weird. The Victorians did not, and that context is important. After all, these were the same people who practiced post-mortem photography—staging photoshoots with dead relatives before burying them. They had radically different norms regarding what was acceptable to capture in a photograph.

But what about Alice herself? What did she think of Lewis Carroll?

As I noted earlier, the rift between Carroll and Alice’s parents lasted only six months, and they resumed visiting each other at the end of 1863. Alice and Lewis Carroll remained friends until his death, and I do find it hard to believe that she would stay in contact with him throughout her adulthood had he been abusive or inappropriate. But then there’s Ina’s commentary to Lennon—was she lying? That, we’ll never know.

In 1932, at the age of eighty, Alice Liddell (now Mrs. Hargreaves) was invited to Columbia University in New York City to celebrate the Lewis Carroll Centenary and to receive an honorary degree. In her acceptance speech, she said, “I shall remember it and prize it for the rest of my days, which may not be very long. I love to think, however unworthy I am, that Mr. Dodgson—Lewis Carroll—knows and rejoices with me.” She went on to lament that Carroll did not write down more of his stories, and that other readers won’t be able to enjoy them.

Whatever the truth of the story may be, it appears that Alice Liddell Hargreaves maintained a positive view of Carroll even into her old age. It’s hard to take off my 21st-century glasses when I analyze these circumstances, but I suppose I can only go by Alice’s recollections that she shared as an adult. After all, she was there.

Our theme song is “Fairy Chase” by Peter Cavallo. Licensing through Artlist.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

Audio Book Club: Chapter 1, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland - Open to all! After a long week, kick off your shoes, pour yourself a cup of tea, and join us around the fire for a relaxing story. Listen here.

Escaping to Elfland - On the legacy of portal fantasy in literature, from The Mabinogion to Lord Dunsany and C.S. Lewis. Read the full story here.

Exclusives for Crossroads patrons:

Patron Podcast: Marie Antoinette - The Early Years - In the first episode of a two-part series, we’ll explore the doomed queen’s early reign, and the problems within the French court that would later fuel the fires of revolution. Listen to the latest episode here.

Last week’s Crossroads Roundup: How the Pyramids Were Built, the World's Oldest Calendar, and a Medieval Village Found in Munich - Our favorite stories on art, archaeology, folklore, and more from this past week. Read the full story here.