The Year Without a Summer

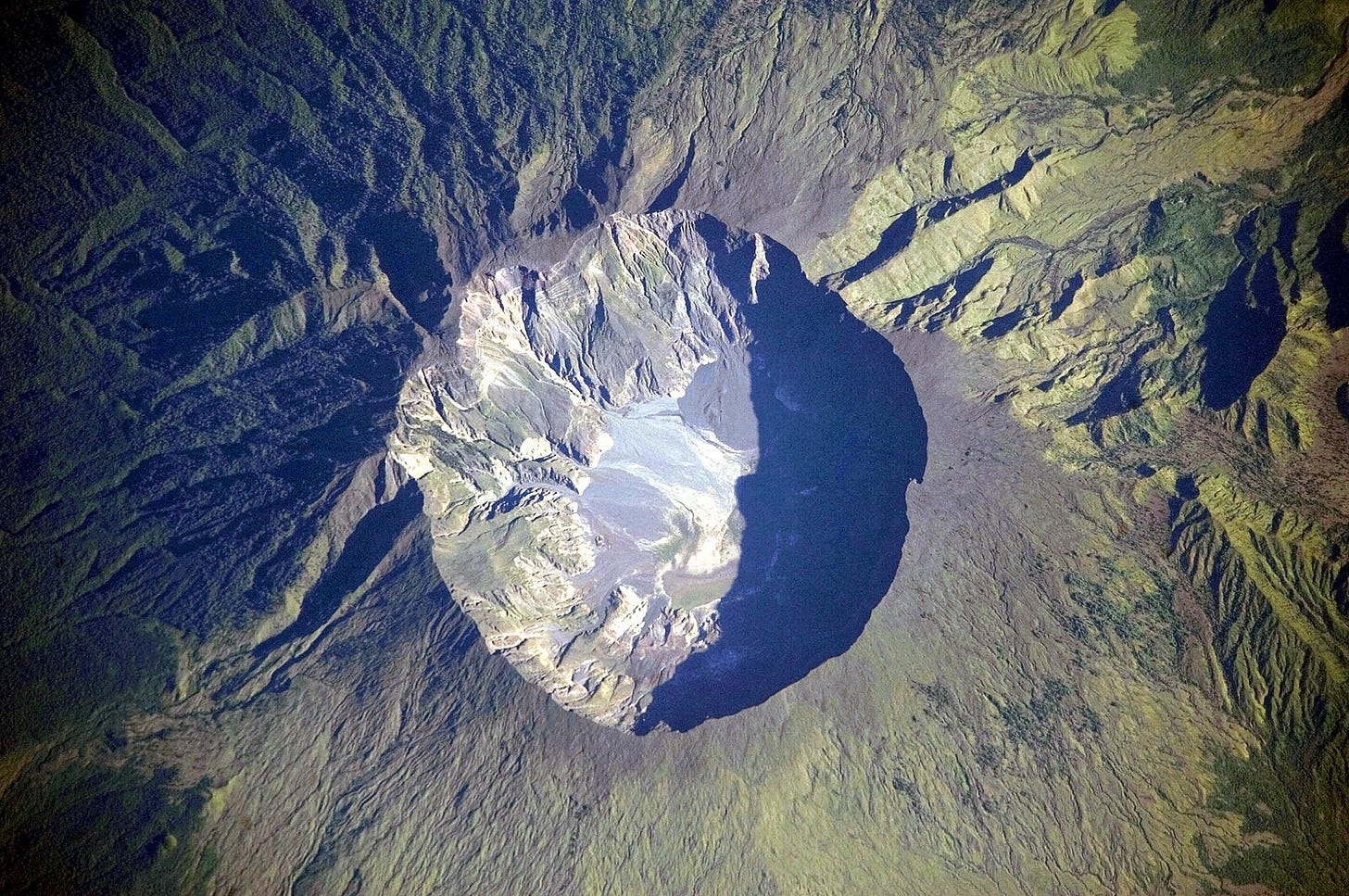

Mount Tambora's 1815 eruption was the largest volcanic event in recorded history, with broad implications for the global climate, agriculture, the arts, and sciences.

This essay is the first in the series The Year Without a Summer. To read future essays in this series and gain access to the full archive, become a paid subscriber today:

The Raja of Sanggar was finishing dinner when he heard the first sign of trouble.

A powerful thunderclap (was it thunder?) reverberated throughout his palace. His servants raced outside to discern the source of the noise.

The sky was ablaze. High on the peak of Mount Tambora, the tallest mountain on the island of Sumbawa, a column of fire shot into the sky. Smoke clogged the view. The sound was deafening.

After three hours, the mountain suddenly fell quiet.

This was April 5, 1815. For several years now, Mount Tambora had issued petulant rumblings. Some of Sumbawa’s peasants speculated that the gods were angry. For the Raja, who ruled the small kingdom of Sanggar on the northeastern part of the island, this was especially troubling, as his subjects might see it as a reflection of his leadership. The island of Sumbawa is part of the Indonesian archipelago, which in 1815 was a hodge-podge of European colonies and agrarian kingdoms. Residents of Sanggar were fortunate to not have attracted the interest of Dutch or British colonizers; nevertheless, more local dangers existed, such as pirates from neighboring islands who regularly kidnapped and sold victims into the slave trade.

The Raja had plenty with which to concern himself. The last thing he needed was a restless Tambora to make his villagers anxious.

Over the next few days, the mountain shook and grumbled. Surely, this would soon wind down.

But a few days later, the peak of Mount Tambora exploded.

The eruption of Mount Tambora on April 10, 1815 remains the largest recorded volcanic eruption in history. Within a few hours, the Sanggar peninsula, including the Raja’s kingdom, was gone. Boiling magma, pumice stones, and ash consumed the nearby villages at such temperatures that victims’ bones turned to charcoal. We know this due to a 2004 archaeological excavation conducted by the University of Rhode Island. Only then was the full magnitude of the eruption uncovered, as the study revealed that temperatures were much higher than those reached by Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. After the 2004 excavation, volcanologist Haraldur Sigurðsson dubbed Tambora the “Pompeii of the East.”1

About ten thousand people died during the immediate eruption, and in the coming weeks, at least 50,000 (though maybe as many as 100,000 people) died of starvation and disease. The ash cloud released by Tambora was so great that it reached the size of the continental United States. Sumbawans, as well as communities on Bali, Lombok, and other neighboring islands, faced devastating famines and poisoned drinking water. The reason we know the details of what happened on that fateful day is because the Raja managed to escape, though not all of his family survived the horrors of the subsequent weeks.

The island of Java to the west was a British colony, and its governor was Sir Stamford Raffles. Raffles was fascinated by Indonesian culture; in his History of Java (1817), he includes an account of Tambora’s eruption.

The English didn’t learn of the famine on Sumbawa until that summer. Raffles responded by sending Lieutenant Owen Phillips on a ship with several tons of rice (a helpful gesture, though nowhere near the amount of food needed to ease the Sumbawans’ suffering). Upon landing on the island, Phillips met the Raja, and he recorded the ruler’s account of the eruption for posterity.

By January of 1816, Europeans began to notice disturbing weather patterns.

That winter, the snow in Hungary was brown. The cold was so extreme that one county in northern Serbia lost 24,000 sheep. In the spring, communities along the Danube faced extensive flooding, destroying fields and agricultural yields. Europe had already suffered a decade of cold winters, matched with the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars. A poor harvest would be devastating.