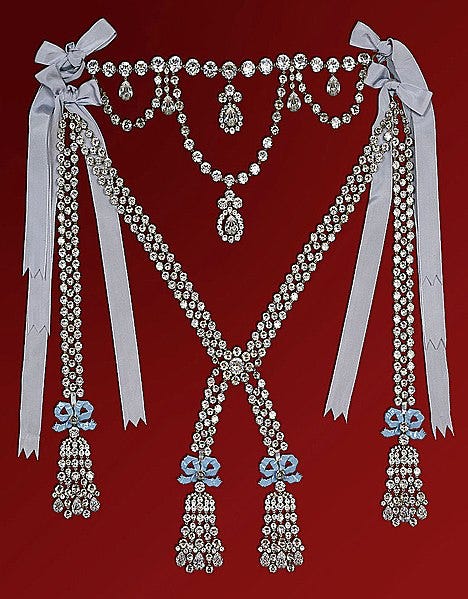

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace

By 1784, Marie Antoinette's reputation was already in decline. But a scandal involving a diamond necklace, a credulous cardinal, and a very cunning thief would launch her down a path of no return.

This essay is part of a series on the life of Marie Antoinette. To gain access to the full archive, become a paid subscriber today:

As every French nobleman at Versailles knew, there were aristocrats in name, and aristocrats in fortune.

Unfortunately for Jeanne de Valois, all she had to recommend her was her family’s name. A descendent of an illegitimate son of Henri II (d. 1559), Jeanne and her siblings otherwise lived hand-to-mouth. Orphans were not looked upon with great kindness in 18th-century France, and when Jeanne begged for food as a child, she pleaded that one might “take pity on a poor orphan of the blood of Valois.”1

By the time she reached adulthood, she managed to prove her ancestry with the court genealogist, negotiate a small pension, and carve out a meager position at Versailles. In 1780, she married Marc-Antoine-Nicolas de La Motte and began styling herself as the “Comtesse de La Motte,” though the legitimacy of the title was dubious at best. Already, Jeanne’s rags-to-riches, fake-it-‘til-you-make-it story seems primed for Hollywood. (All aristocratic titles begin in fabrication, anyway; let the woman be a countess if she so desires!) But Jeanne wanted more, and her scheming would have a major impact on the life of Marie Antoinette—and indeed, the institution of the monarchy in France.

When we last left Marie Antoinette, we discussed the roots of her demise: her delay in producing an heir, rampant royal spending (much of which wasn’t her fault), the loosening of court etiquette (which made her even more unpopular at court), and her inept political meddling. Regrettably, her early forays into politics were fueled less by strategy and more by personal resentments. By the early 1780s, her popularity had deeply declined.

In other words, she was the perfect target.