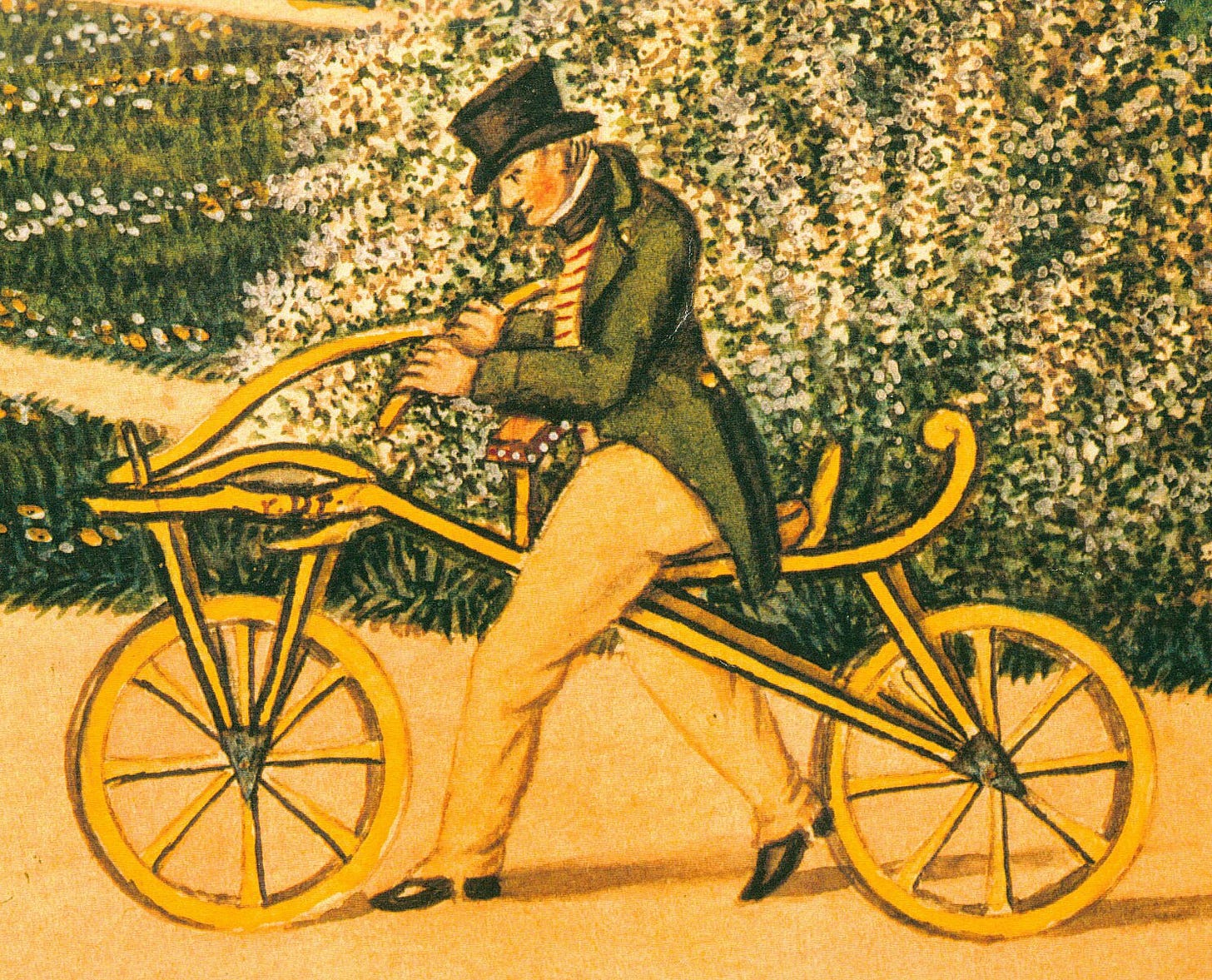

How a Volcano Gave Us the Bicycle

From the invention of the "running machine," to the birth of meteorology, let's examine a few bright spots that appeared after Tambora's tragic eruption.

This essay is part of the series The Year Without a Summer. To read future essays in this series and gain access to the full archive, become a paid subscriber today:

Only one person in history has left a paper trail of both the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 and Europe’s Year Without a Summer.

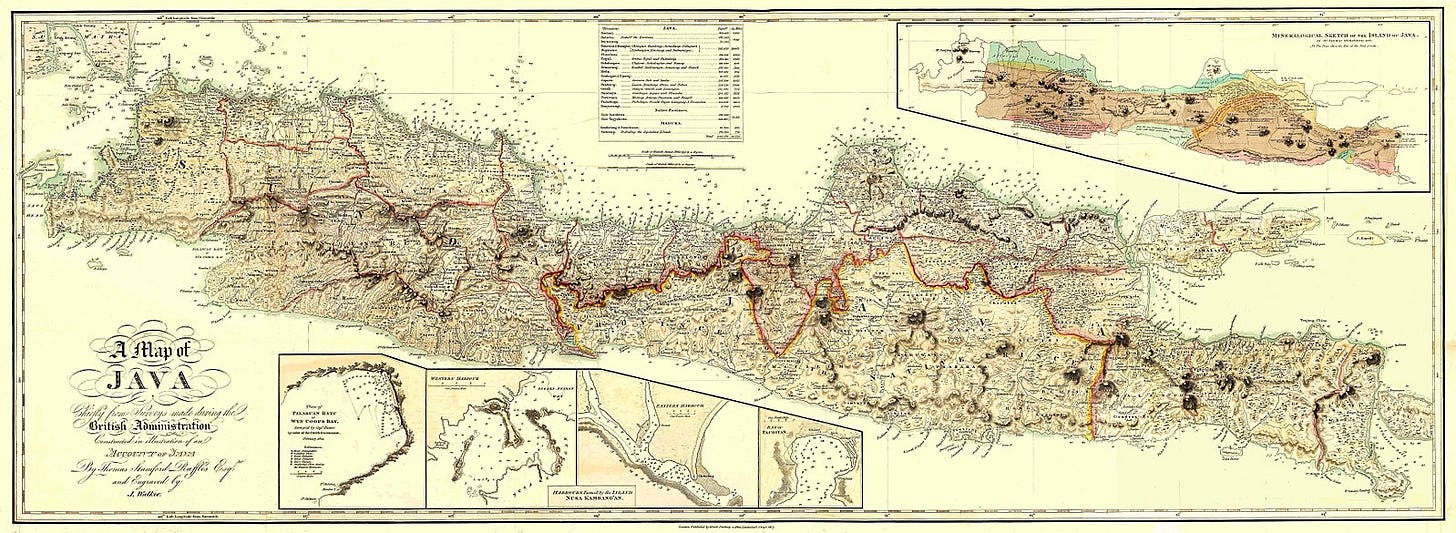

Readers may recall Stamford Raffles, governor of the British colony of Java and author of History of Java (1817). Raffles’s account of Tambora is shockingly brief given the magnitude of the disaster: a mere footnote after an essay on Java’s “Mineralogical Constitution.” This makes more sense when one considers that Raffles was lobbying for expanded colonization of Southeast Asia, particularly to compete against the Dutch East India Company. Offering gory details of a volcanic eruption on an island just 200 miles away could prompt his audience to ask pesky questions. Are there other active volcanos in the region? Could the same event happen again?

Throughout his life, Raffles pursued his goal of colonizing more land in the region for the British Empire, including establishing the colony of Singapore in 1819. But in 1816, he was compelled to return to England to explain Java’s poor financial management. When he wasn’t fighting allegations of fraud, he was doing what many young, rich men of the era did to pass the summer—traveling the European continent.

In previous eras, the Grand Tour was a rite of passage for upperclass men when they came of age. Raffles’s early twenties coincided with the Napoleonic Wars, making the Grand Tour difficult, if not impossible. Now turning thirty-five, Raffles and his peers could once again explore the countries of Europe in the fair weather of summer.

Except, as we know, the summer of 1816 was a season unlike any Raffles had witnessed.

Raffles was accompanied by his brother Thomas, who wrote of their experiences in his journal. He noted that the villages of France were overwhelmingly deserted:

We could not but notice the almost total absence of life and activity… There was an air of gloom and desertion pervading them. The houses had a cheerless and neglected appearance. No one was seen in the streets—they looked as if deserted by their population.1

In the years 1816 and 1817, crop yields in Western Europe and the British Isles dropped by 75%. We investigated the ramifications of agricultural failure in Europe and in Asia in my previous essays; for today’s entry, I’d like to explore a few glimmers of hope.