Claude Monet Goes Abroad

This week in "Claude Monet: The Art of the Series," we turn to the artist's work in London and Venice.

This is the third essay in Claude Monet: The Art of the Series.

In 1834, a fire burned most of the United Kingdom’s Houses of Parliament to the ground. Westminster Hall, built in 1097, was salvageable—a miracle, thanks to the efforts of brave firefighters and a change in the winds.

Once the ashes settled, it grew obvious that rebuilding would be a tremendous undertaking. A committee in each House decided to host a contest, in which architects could submit plans for a revamped Palace of Westminster. At the time, the Classical style was the norm for British state buildings. But Charles Barry had a bold idea: he submitted a design in the Gothic Revival style. After all, England wasn’t unified until the late 900s; the Gothic seemed a more fitting choice for Parliament’s new home. Barry won the contest, and he soon recruited Augustus Pugin, an architect who believed that the Gothic was the only truly acceptable style for a Christian nation.1

The entire project wouldn’t be finished until 1870, by which time Barry and Pugin had both passed away. While the Palace of Westminster clearly paid homage to Britain’s medieval past, its construction included modern developments. Its central tower was designed as a ventilating chimney, making it one of the world’s earliest artificial ventilation systems, and its clock tower (famously known as Big Ben) was the most accurate clock of its kind when it was completed in 1859.2

Claude Monet first arrived in London in 1870, just in time to see Barry and Pugin’s final masterpiece. It was four years before the First Impressionist Exhibition would shock Paris, though gallery shows were likely the furthest thing from Monet’s mind. He and his first wife Camille were among the many refugees of the Franco-Prussian War who had temporarily relocated to Britain.

The Monet family lived at 11 Arundel Street before moving to Kensington. Monet often ventured to the nearby River Thames, and he grew captivated by scenes of daily life along its banks. During these early years, Monet greatly struggled to sell his work. But as fate would have it, the Barbizon landscape painter Charles-François Daubigny was also waiting out the war in London, and he had been successful in selling his own paintings of the Thames. He told Monet, “I know what you need. I’m going to get you a dealer.”3

The following day, Daubigny introduced Monet to Paul Durand-Ruel.

Over thirty years later, Monet was now a famous artist, and Durand-Ruel was the mastermind who had ushered the Impressionists onto the global stage. Eager to discover new subjects, Monet began to travel abroad around the turn of the century. His trips to London and Venice gave him ample material, and both allowed him to explore his love of painting bodies of water. Additionally, his house at Giverny was growing crowded with in-laws and grandchildren. At the start of the new century, he took the opportunity to return to London, this time painting from the balcony of his room at the Savoy Hotel, or from a window at St. Thomas’s Hospital.4

Like his Rouen Cathedral series, Monet’s Houses of Parliament paintings lent a fairytale aura to a great, Gothic structure. It’s clear how much his style had evolved when comparing these works to those created during the Franco-Prussian War. Unlike the Rouen paintings, his Houses of Parliament went beyond the architecture to convey the haziness of London’s fog, such that one can’t tell where the water ends and the sky begins.

To effectively showcase various light conditions, Monet worked on multiple canvases at once, stopping and moving onto the next when the light changed. He explained this process to Durand-Ruel in a letter from March 23rd, 1903:

I cannot let you have a single London picture, since it is essential that I have them all before me, and, to be honest, not one of them is finished. I am working on them all together.5

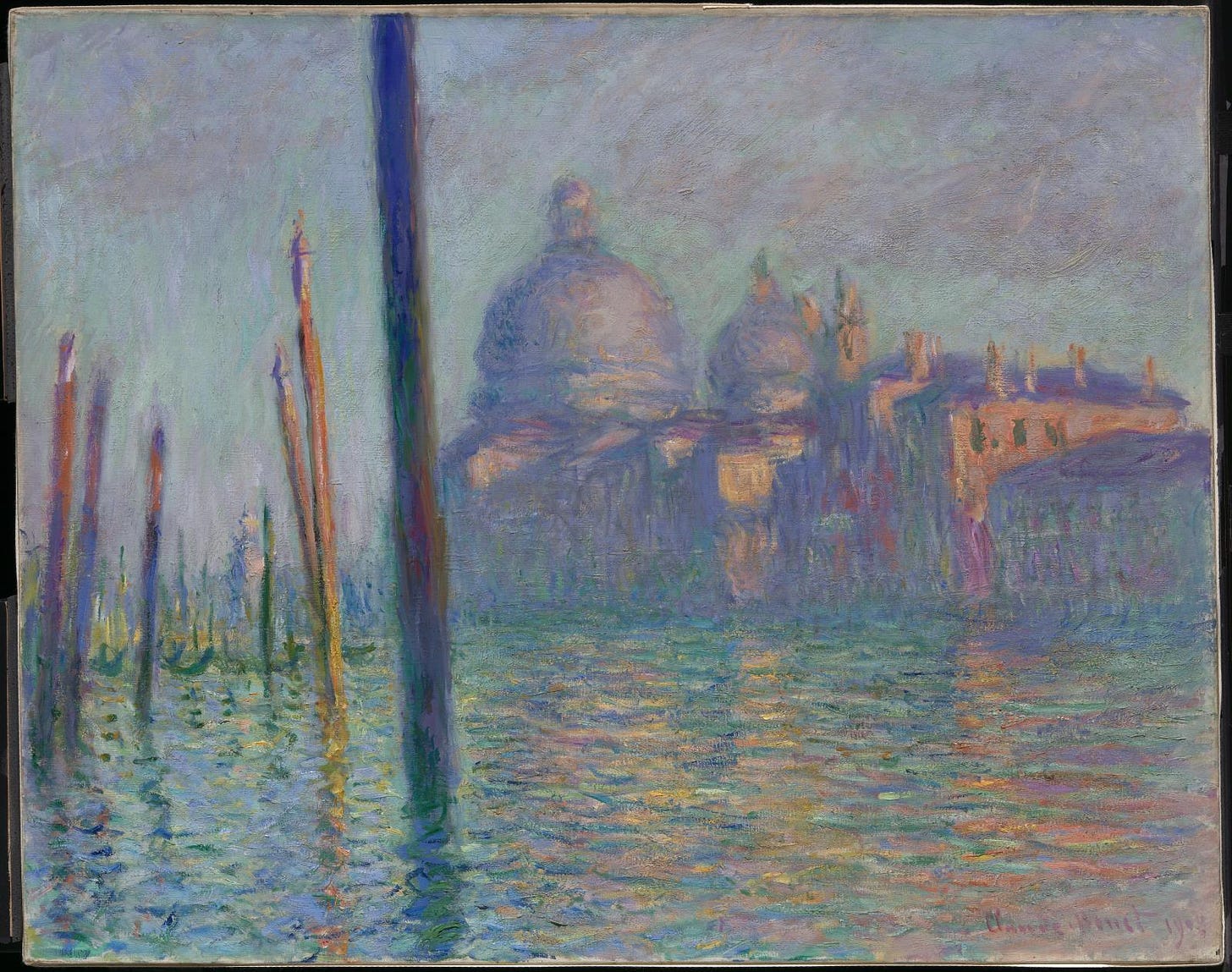

In 1908, Monet and his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, were invited by John Singer Sargent to join him for two weeks at the Palazzo Barbaro, situated along the Grand Canal in Venice. After a few days of sightseeing, Monet grew so consumed with a series of the Grand Canal that Alice was concerned. She wrote to her daughter Germaine on December 3rd, “It is high time he relaxed. He is working very hard, especially for a man his age.”6 (Monet was now sixty-eight years old.)

But Monet had no such plans. As with the Houses of Parliament, he painted the Grand Canal at all hours, only stopping his work after sunset. However, his process had changed since his early years. Monet still began his works en plein air, but especially when traveling, he stopped and finished them in his studio at Giverny. The fantastical quality of these paintings could apply not just to their pastel colors but to the question of the scenes’ “truthfulness.” (Was the water in the canal really such a sparkling blue in the dead of winter?) In that sense, we are missing the “instantaneity” of his Haystacks, though in exchange, we receive greater insight into the artist’s subjective experience. These works are a marriage between the initial light and weather conditions of each piece’s early stages and Monet’s memories from his travels as he finished them at Giverny.

So far, we’ve covered several of the artist’s most important series and followed him across Europe. But there is a subject that occupied so many of his works that I can’t possibly fit them into a single essay.

As Monet painted his Haystacks and Poplars, as he traveled throughout France and beyond, there was one series to which he continuously returned, resulting in roughly 250 paintings. For the last two essays of this series, we will visit Claude Monet in his garden at Giverny, and of course, his water-lily pond.

Speaking of medieval inspiration…

Recently on Fireside Fables: Why We Don’t Build Castles Anymore

This week on Fireside Fables, we discussed the rise and fall of the castle, its fairytale resonance, and why the Victorians led a brief comeback of this iconic style of architecture.

“Gothic Revival” in Architecture: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Kathryn Hennessy, Anita Kakar, and Angela Wilkes (DK, 2023), 252-253.

“Gothic Revival,” Architecture, 253.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Vintage, 2006), 82.

Christoph Heinrich, Monet (Taschen, 1994), 67.

Heinrich, Monet, 68.

Heinrich, Monet, 70.