Camille Pissarro Finds His Voice

"One must have only one master—nature; she is the one always to be consulted."

This essay is part of an ongoing series celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition, which debuted in Paris in 1874. If you’d like to read other essays on the history of Impressionism, you can do so here.

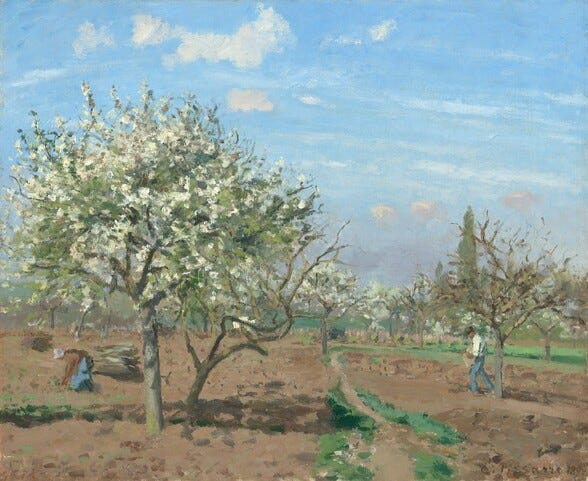

The Chestnut Trees at Osny (1873) is one of my favorite works of art. Painted by Camille Pissarro in 1873, it was featured in the notorious First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874, when the Impressionists shocked Parisian society with their loose, radical style and “vulgar” portrayals of ordinary life.

My reasons for loving this painting are more personal. When I look out the window this time of year, the trees appear much like those in Pissarro’s landscape.

Here in Nashville, we have finally reached late summer, and we have about a month of hot weather ahead of us before approximating anything that resembles autumn. The trees, a vivacious emerald in May and June, have matured into a golden olive. As I write on a picnic blanket at a local park, a light breeze cutting through the humid afternoon, I can close my eyes and fly away to Pissarro’s scene in rural France.

Camille Pissarro possessed an extraordinary love of nature. As he wrote to the young artist Louis Le Bail in 1897:

Paint generously and unhesitatingly, for it is best not to lose the first impression. Don’t be timid in front of nature: one must be bold, at the risk of being deceived and making mistakes. One must have only one master—nature; she is the one always to be consulted.1

While his style evolved greatly over the course of his life, his love of the outdoors remained constant. Even as he began losing his eyesight in his final years, and working en plain air grew challenging, Pissarro would set up his easel by the window to capture the view. But what struck me as I read his letters and learned about his life was his strength of character and genuine warmth, which carried him through the many hardships he experienced.

John Abraham Camille Pissarro was born in 1830 to a Jewish family in Saint Thomas, then part of the Danish West Indies. His father Frederick was of Portuguese descent; Frederick had moved to St. Thomas from France to take over his late uncle’s hardware store. In a rather controversial move, Frederick married his uncle’s widow, Rachel—an act that is against Jewish law. (The local synagogue didn’t formally acknowledge the marriage for many years, after the couple already shared four children.)2

The young Camille was sent to boarding school in France as a teenager. His drawing lessons proved incredibly influential, and while he would return to St. Thomas upon completing his studies, he longed to move back to France to pursue a career as an artist. The death of his father at nineteen may have further motivated his desire to leave the Caribbean, as Pissarro was deeply impacted by this loss.

By the late 1850s, he had moved to Paris with his mother, his older half-sister Emma, and Emma’s children. Camille fell in love with the café-culture of Montmartre, where he could freely discuss his anarchist politics and passion for social justice. It was also at this time that he befriended Claude Monet at Martin François Suisse’s studio; like Monet, he would swiftly grow frustrated with the limitations of academic art.3

A pivotal moment arrived in 1860, when Pissarro’s mother hired a maid named Julie Vellay. Pissarro was captivated by her outspoken personality and passion for worker’s rights. Their romance was complicated by Vellay’s pregnancy, but the couple ignored the protests of Pissarro’s family and eventually got married. His family’s reservations mattered little: Pissarro was loyal and devoted to his wife until his death, and the strength of their relationship helped them get through the ups and downs that would follow.

One infamous example was when the Pissarros moved to London in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. Camille and Julie had just suffered the loss of a baby girl, and while Camille initially intended to remain in France, this loss clarified the need to seek out safety for Julie and the rest of their children. He left about a thousand paintings behind in France, and when he returned, he found that they had all been destroyed by Prussian soldiers. The soldiers had occupied his house in Louveciennes during the war, and they used his canvases as duckboards.4

As we’ve established throughout this Impressionism series, the early years for our Impressionists were mired by rejection and financial obstacles. While Pissarro was able to place paintings at the Salon, he wanted to showcase the new, experimental styles evolving from the bohemian enclave of Montmartre. He was the oldest of the Impressionists, and younger painters like Paul Cézanne and Mary Cassatt would see him as a trusted advisor, always ready to offer his encouragement.

It was Pissarro, alongside his friend Monet, who would spearhead the formation of the “Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.”—the rebel society who would host the first Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.5

What was it that prevented Pissarro from becoming a greater success in his lifetime?

The other artists we’ve examined thus far in this series—Manet, Monet, Morisot—all enjoyed varying degrees of success when they were alive. Manet was a celebrity, Monet died wealthy after years of struggle, and though Morisot faced many obstacles on account of her gender, she was still able to sell a good number of paintings, particularly later in life.

While Pissarro achieved recognition during his lifetime, he faced difficulties in selling his work. In 1903, the year he died at the age of 73, he managed to sell two paintings to the Louvre.6 In my view, Pissarro’s problem was that he was wildly ahead of his time, while also coming to these radical discoveries at an older age.

For example, Pissarro was about ten to fifteen years older than most of the Impressionists. This age difference, along with his kind demeanor, allowed him to effectively mentor everyone from Cassatt and Cézanne to Gaugin and Van Gogh. But this also meant that he would die before the styles he pioneered would have a chance to truly take off.

One such instance was his temporary embrace of Neo-Impressionism, a new school of thought pioneered in the 1880s by artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Seurat aimed to develop a theoretical, scientific system for painting that in practice relied on pointillism. While Seurat’s life ended tragically at the age of thirty-one, masterpieces like A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte would prove enormously influential.7

Pissarro experimented with pointillism for several years before abandoning the technique and Neo-Impressionism more broadly. In a letter to the artist Henri Van de Velde, written on March 27th, 1896, Pissarro sharply critiqued the movement:

I can no longer consider myself one of the Neo-Impressionists who abandon movement and life for a diametrically opposed aesthetic which, perhaps, is the right thing for the man with the right temperament but is not right for me, anxious as I am to avoid all narrow, so-called scientific theories. Having found after many attempts (I speak for myself), having found that it was impossible to be true to my sensations and consequently to render life and movement, impossible to be faithful to the so random and so admirable effects of nature, impossible to give an individual character to my drawing, I had to give it up. And none too soon!8

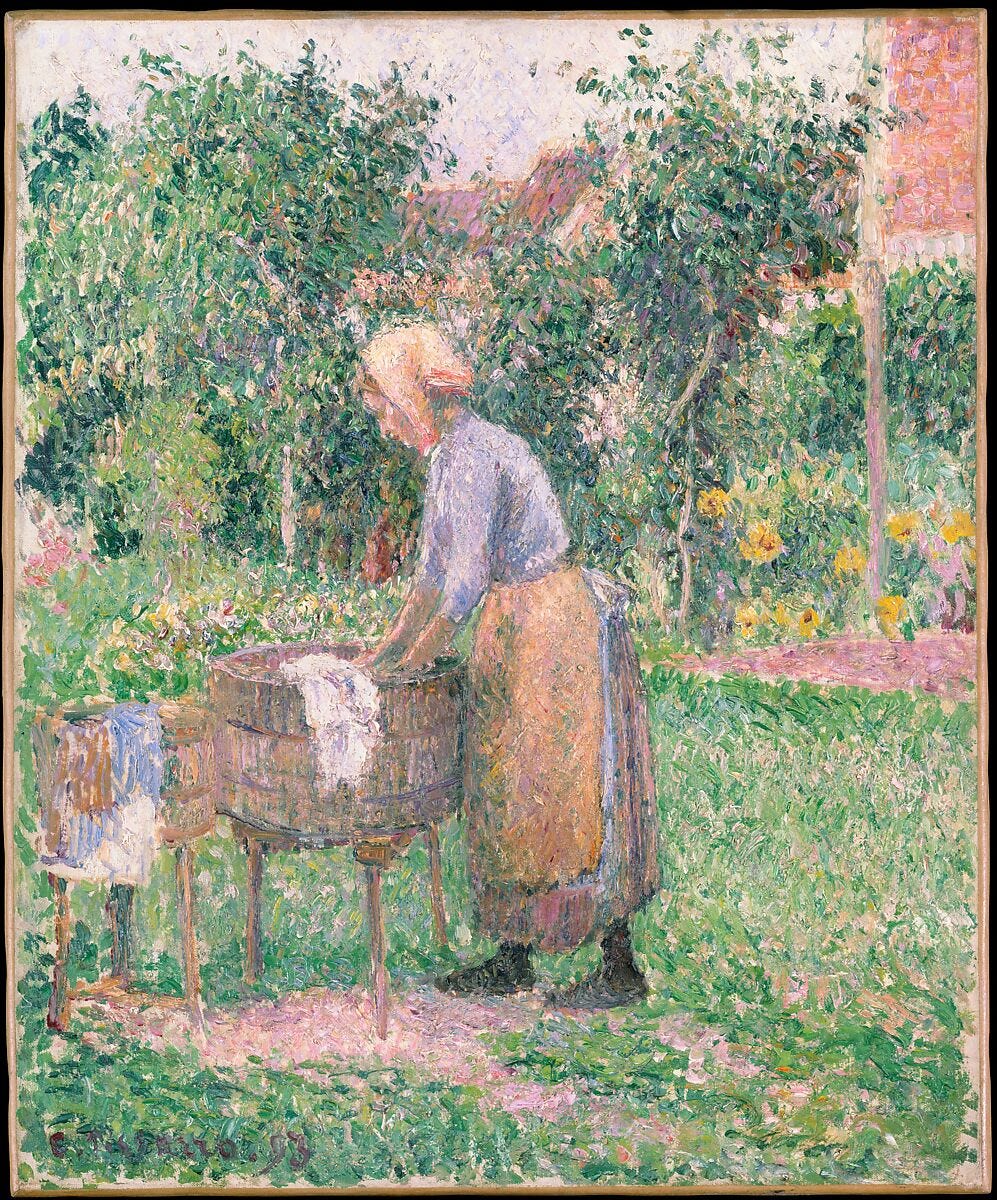

Leaving Neo-Impressionism in the final years of his life, Pissarro’s work was reinvigorated by his passion for nature. It is within these later works that one can see the culmination of years of experimentation (and his mentees greatly benefited from that experience). In his iconic street scenes, which he captured from windows of various hotel rooms around Paris, Pissarro seemed to have truly found his voice. He could apply the ideas he had learned from his Neo-Impressionism phase without abandoning the depths of emotion and natural instincts that embodied his earlier works.

As Pissarro discovered, scientific rationalism has its limits. To be a true artist, one must dare to feel.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

Berthe Morisot: the Great Lady of Impressionism - “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal and that’s all I would have asked for, for I know I’m worth as much as they.” Read the full story here.

Manet at the Café - “Never will he completely overcome the gaps in his temperament, but he has temperament, that is the important thing.” Read the full story here.

Exclusives for Crossroads patrons:

Patron Podcast: Marie Antoinette - The Early Years - In the first episode of a two-part series, we’ll explore the doomed queen’s early reign, and the problems within the French court that would later fuel the fires of revolution. Listen to the latest episode here.

Last week’s Crossroads Roundup: A Fake Da Vinci, a Major Stonehenge Discovery, and Yayoi Kusama - Our favorite stories on art, archaeology, folklore, and more from this past week. Read the full story here.

Linda Nochlin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism 1874-1904: Sources & Documents (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966), 60.

Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (London: Vintage, 2006), 13.

Roe, Private Lives, 14.

“Camille Pissarro” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 352.

Roe, Private Lives, 119.

Roe, Private Lives, 268.

“Georges Seurat” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 363.

Nochlin, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 59.

Congratulations on another really brilliant edition of this series, Nicole.

Such a great tribute to a man who definitely deserves a lot more credit than he gets sometimes.

As you say, the influence he had on pretty much all the key impressionists (and post impressionists too) is really remarkable. But I also love the stories of how he was just generally a really kind and generous person too.

YAY! I went to the 150th Anniversary of the First Impressionism Exhibition in Paris. It will be in DC at the National Gallery of Art this fall.