A Midsummer Nightmare?

William Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream" includes one of the most famous literary depictions of fairies. How do Oberon and Titania compare to the fairies of Elizabethan folklore?

This essay is part of a series called On the Origin of Fairies. To gain access to the full archive, become a paid subscriber today:

Years ago, I saw a very odd production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater.

It was a 1970s-meets-medieval(ish)-meets contemporary extravaganza, an acid trip with vibrant colors and disco dancing. Like all bad Shakespeare productions, the show lacked a clear artistic direction—it didn’t know what it wanted to be. The best one could say was that the fairies were fabulously costumed, as you can see below.

(No hate to Chicago Shakespeare! I’ve seen some truly remarkable adaptations there. This wasn’t one of them.)

The beauty of Shakespeare’s writing is that the conflicts and themes present in his work transcend time, such that theater directors today can employ whatever setting or costume direction speaks to them. But Shakespeare’s fairies can also give us some insight into differing views of the Good People in a period when almost everyone believed in spirits.

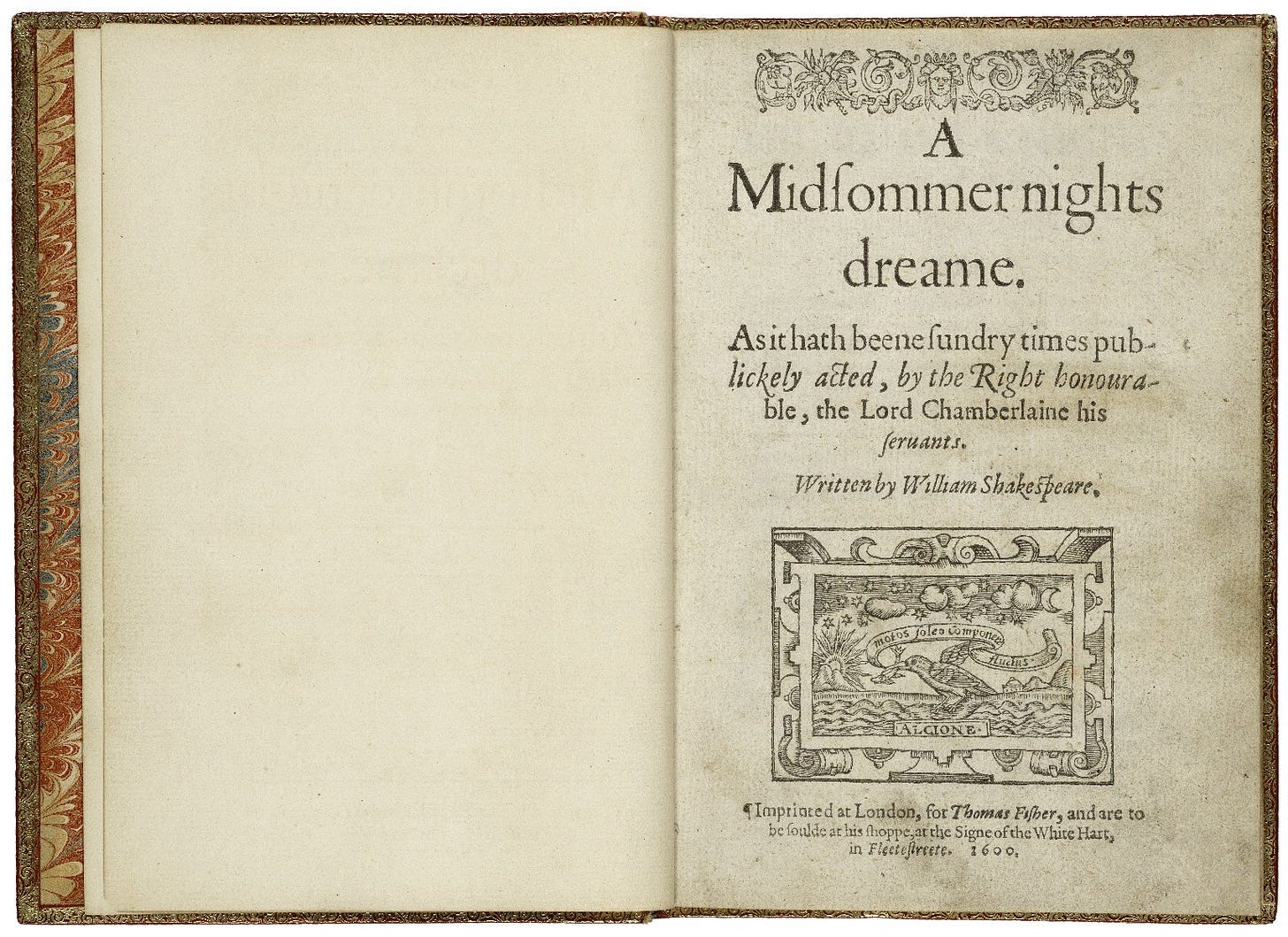

Scholars don’t have a precise date for when A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written, though it is generally estimated to date from 1594 to 1596.1 The fairies in the play are not quite as malicious as those of Elizabethan folklore. Midsummer is a romantic comedy, after all, and the fairies seek to undo the trouble they’ve caused by the end of the show. Oberon and Titania’s squabbling (not to mention, their interference with the human characters’ love lives) is much more reminiscent of the Greek pantheon’s antics than the wild, weird world of fairy lore.

Shakespeare adapts the Greek myth of Pyramus and Thisbe for the play performed at the wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is set in Athens. Needless to say, the Greeks were on the mind. But some aspects of the play come straight out of British folklore. After all, the root of the conflict between Oberon and Titania—the argument that launches much of the play’s action—is over a changeling.

As Robin Goodfellow (Puck) informs a member of Titania’s fairy court in Act 2 Scene 1:

The King doth keep his revels here tonight.

Take heed the Queen come not within his sight,

For Oberon is passing fell and wrath

Because that she as her attendant hath

A lovely boy stolen from an Indian king—

She never had so sweet a changeling—

And jealous Oberon would have the child

Knight of his train, to trace the forests wild.2

Shortly after, the fairy recognizes Robin Goodfellow as an infamous fairy spirit:

Fairy: Either I mistake your shape and making quite,

Or else you are that shrewd and knavish sprite

Called Robin Goodfellow. Are you not he

That frights the maidens of the villagery,

Skim milk, and sometimes labor in the quern,

And bootless make the breathless housewife churn,

And sometime make the drink to bear no barm,

Mislead night-wanderers, laughing at their harm?

Those that “hobgoblin” call you, and “sweet puck,”

You do their work, and they shall have good luck.

Are you not he?

Robin: Thou speakest aright;

I am that merry wanderer of the night.3

This has become familiar territory in the most recent entries of our series: a stolen child, a trickster spirit, and a reason to call a “knavish sprite” a “sweet puck”—because appeasing a dangerous fairy can sometimes bring good fortune. (Phrases like the Good Folk, the Good People, and the Gentry come to mind.)

The word “puck” is derived from the Indo-European root *bheug- (“to flee in fear, be frightened of”), which in Old English became “puca,” and in Middle English “pouke.”

This root is also the wellspring of other words such as the Irish púca and the Welsh bwg (pronounced “boog”).4 In the late Middle Ages, pouke was the common word for “fairy” in southern England before the introduction of the French “fée.” At the end of this series, we will examine the possible merging of Norman and Anglo-Saxon folklore after the Norman Invasion, and how this could have resulted in the emergence of the unified group we now call fairies.

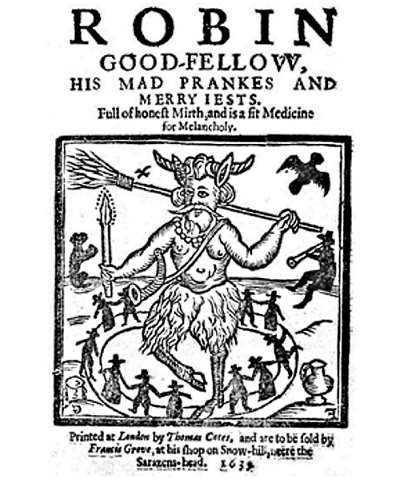

In any case, this process was complete by the time William Shakespeare was writing A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Pucks were a class of pesky, trickster fairies; Robin Goodfellow is the preeminent puck of Elizabethan folklore. The earliest known reference to Robin Goodfellow comes from the 1584 Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow (author unknown), but it’s possible that the character predates that text.5