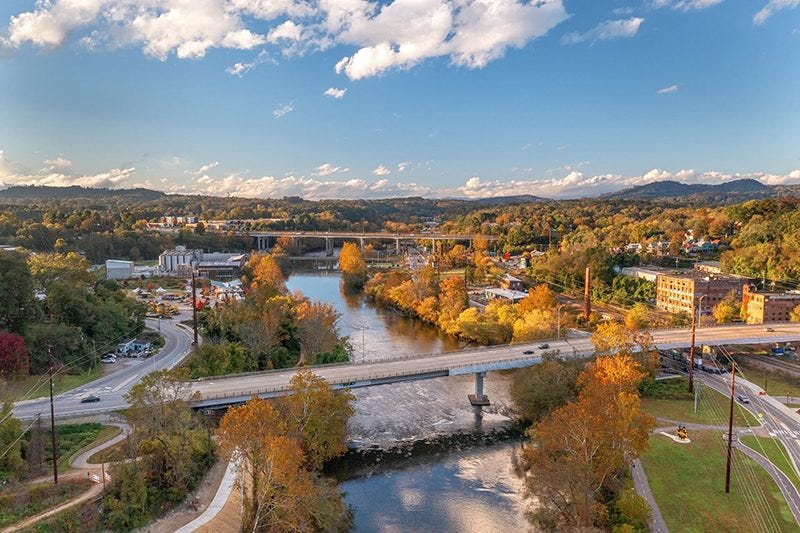

The River Arts District: Asheville, NC

In the wake of the devastation of Hurricane Helene, let's discuss the history of the River Arts District and why Asheville is such an important city for American artists.

Rivers are ephemeral beings in the long march through time. The Earth lives on, but its rivers shape-shift and evolve; their waters mold the landscape as an artist molds clay.

Some disappear from the map while others endure. The French Broad River, which cuts through the Blue Ridge Mountains, is a grand old-timer at 320 million years old. It’s seen everything: 10,000 years of Cherokee habitation, followed by British colonization and the establishment of the United States, the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, the railroads and boomtowns of the Industrial Revolution. The brutal exploitation and later decline of coal mining. Long before the Digital Age, the riches of industry had largely retreated to glittering enclaves in New York and Philadelphia, and the people of the mountains were left to fend for themselves.

Anyone who has lived or traveled through the region knows that in …