The Glasgow Style

At the turn of the century, a group of forward-thinking artists in Glasgow spearheaded the British Art Nouveau movement.

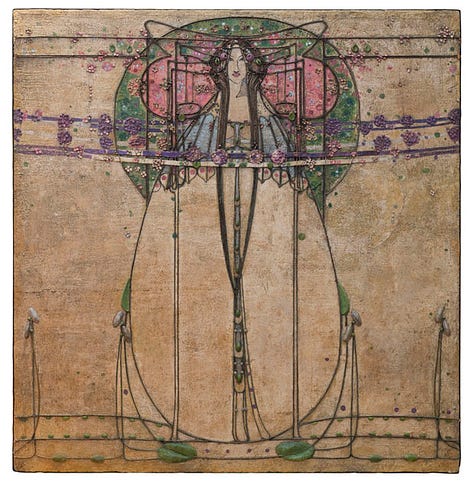

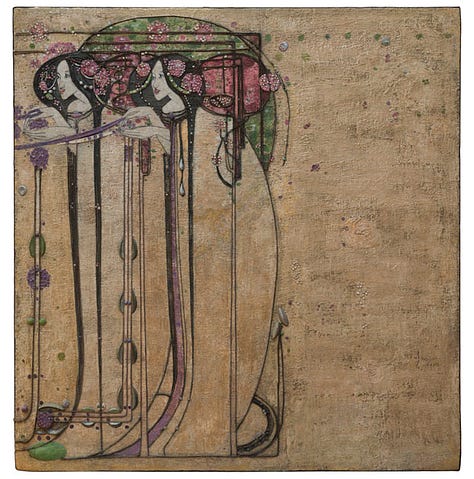

The May Queen stopped me in my tracks the first time I saw it. Combined, its three panels stretch fifteen feet in length, and each are over five feet tall. From a distance, it transported me to an Arthurian castle—a tapestry fit for a fairy realm.

As I drew closer, I could better discern its diverse materials. The panels were made of gesso on burlap, lending them a rich texture. Gesso, if you’re unfamiliar, is a white paint blend traditionally comprised of chalk, white pigment, and an animal glue binder. (Today, acrylic gesso is cruelty-free.) The composition was decorated with tin leaf and glass beads; twine brought the Celtic-inspired line work to life.

Four women (fairies?) attended to the May Queen. All ethereal beauties with flowers in their hair.

The May Queen (1900) was created by Margaret Macdonald for the Ladies’ Luncheon Room at the Ingram Street Tearooms in Glasgow. Here, we have a wom…