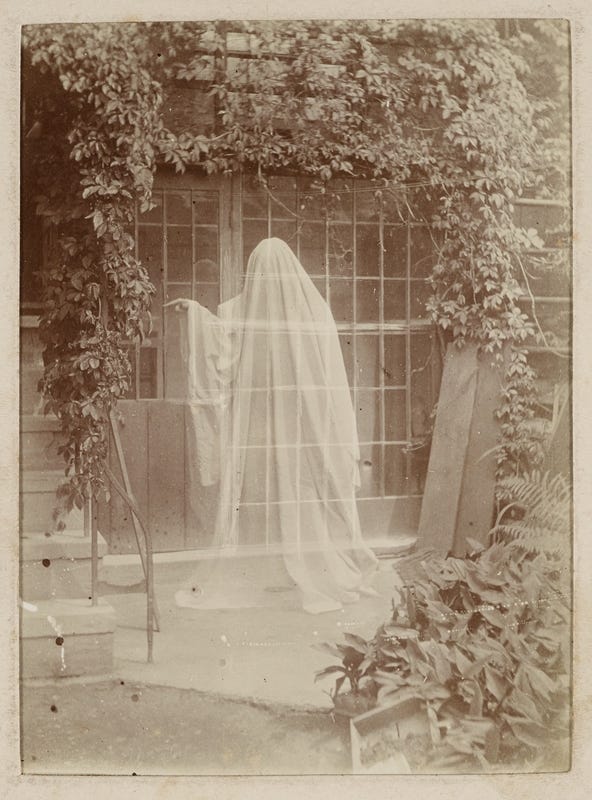

Psychics, Mediums, and Spiritualists

Beginning in the mid-19th century, Americans and Brits grew obsessed with ghosts. Inside the Spiritualist movement: its origins and its lasting impact.

1848 was a year of upheaval in the Western world. Revolutions spread throughout Europe, as the people of Italy, France, the Netherlands, the Austrian Empire, and the German Confederation fought to overthrow archaic monarchies and abolish the remnants of feudalism.

In the United States, a quieter revolution was taking place. The call came not from peasants fighting for the end of serfdom, nor from citizens looking to topple a king: in the hamlet of Hydesville, New York, the message arrived from beyond the grave.