Frankenstein, Yunnan, and the Opium Trade

The Year Without a Summer inspired authors from England to Southwestern China. But horrific famines would also compel farmers to turn to a lucrative, addictive cash-crop.

This essay is part of the series The Year Without a Summer. To read future essays in this series and gain access to the full archive, become a paid subscriber today:

Thousands of miles apart, two very different writers were witnessing a climate emergency of epic proportions.

In Geneva, Mary Godwin (soon-to-be Shelley) planned to pass the summer of 1816 in tranquility with her lover, Percy Shelley, their friend Lord Byron, Byron’s doctor John William Polidori, and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont, then pregnant with Byron’s child. Instead, she witnessed dismal, punishing rain, and a local populace who would soon face devastating circumstances if the weather didn’t turn around.

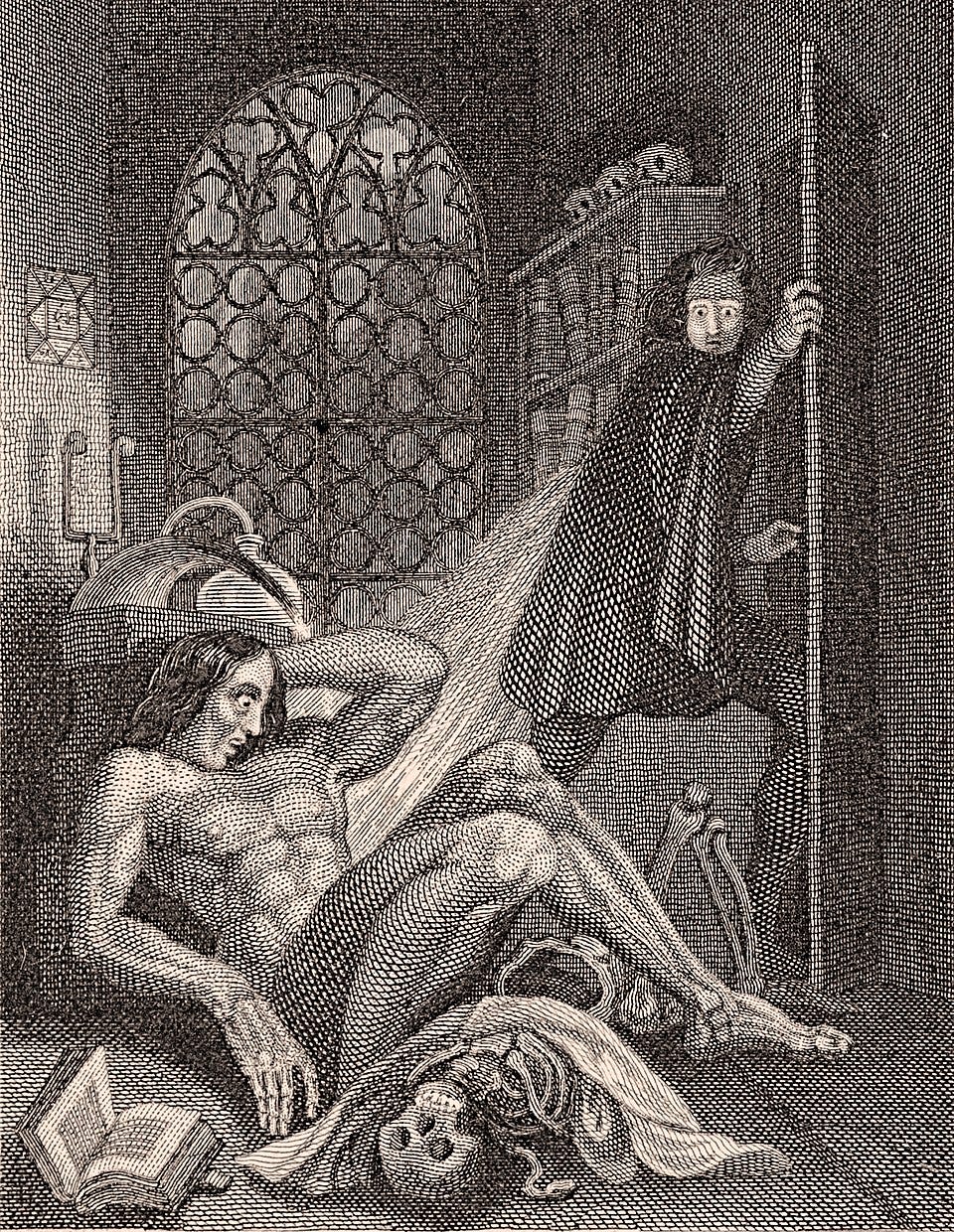

Between April and September of 1816, it rained 130 days in Geneva, resulting in floods and ruined summer crops. The extreme cold that had befallen Europe after the eruption of Mount Tambora also caused the growth of Alpine glaciers, which encroached upon agricultural fields and conjured fears of an ice age. Thunderstorms became the soundtrack of Mary Shelley’s holiday. Dark, stormy nights, lashing rain… the setting was downright Gothic, ripe for the birth of what many scholars consider to be the first science fiction novel.

I’ve written before about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the ghost-story competition that catalyzed her creation. But the horrors Shelley invented for her novel were no match for the trauma inflicted on Europe’s peasants that year. The meteorological impacts of Tambora stretched into 1818; the “Year Without a Summer,” though a famous moniker, is therefore incomplete in encapsulating the people’s suffering.

Note that this was prior to the spread of railway lines across the continent, which made transporting food to hard-hit areas a logistical nightmare. The wealthy Shelley circle were financially insulated from such trials, but the vast majority of people still relied on the land for food and income. In Switzerland, the fragmented political system made it even more difficult to respond to the crisis. With grain prices now two to three times higher than in coastal areas, the Swiss saw an explosion of famine that caused deaths to exceed births in 1817 and 1818.

One wonders if Frankenstein’s monster received his ghastly visage as a result of these events. A priest from Glarus described the conditions of his Alpine community: