Crossroads Roundup: Possible Van Gogh Found, the Home of the Last Anglo-Saxon King of England, and Gustav Klimt

The latest news in art, archaeology, culture, and more.

It’s been a month since my last Roundup, and the beginning of the year has certainly been busy:

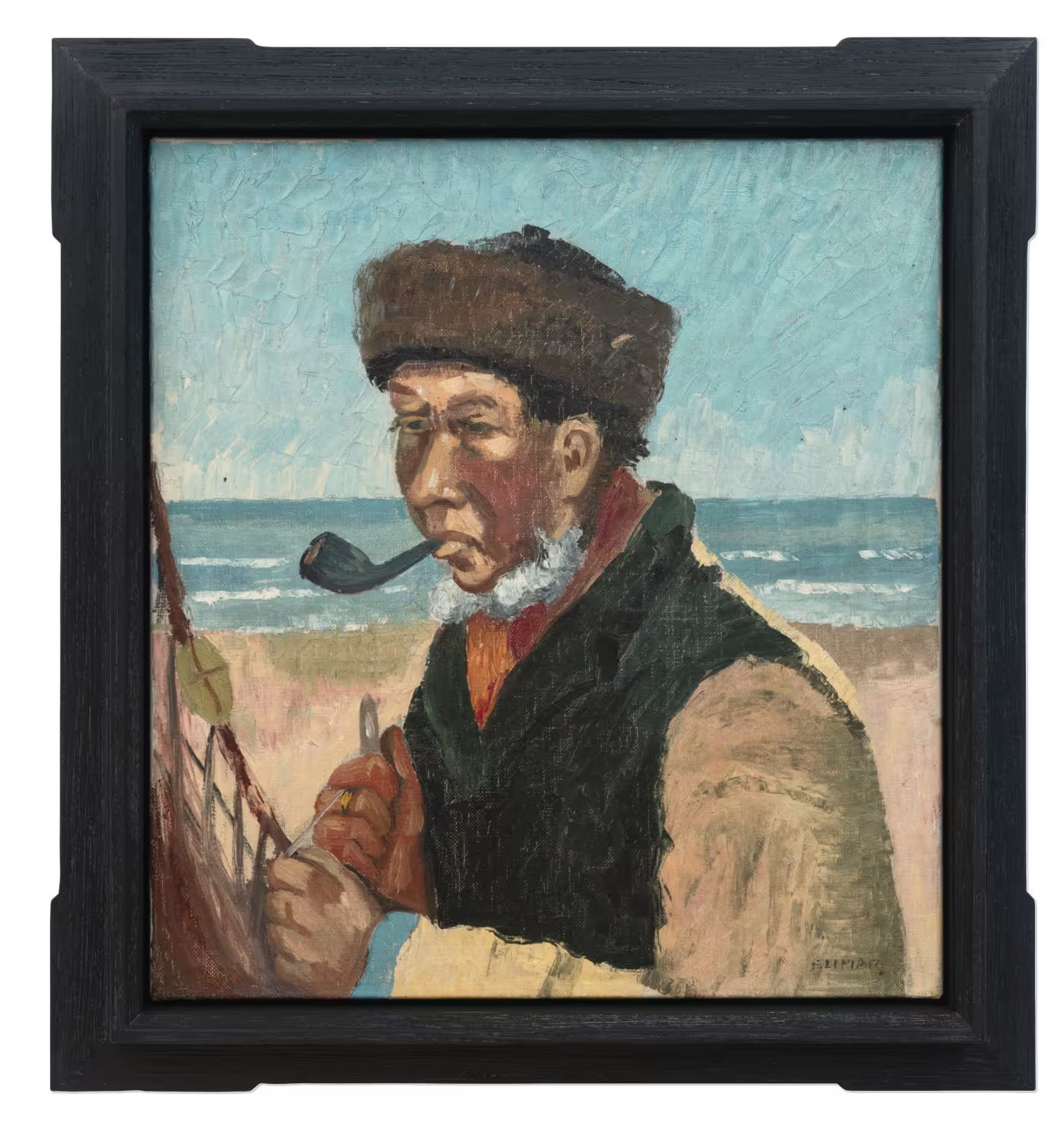

A real Van Gogh found at a garage sale? LMI Group International says yes. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam says no.

Some of you may recall the drama over Salvator Mundi, a painting that was authenticated as an original work by Leonardo da Vinci, despite objections from some experts. A similar case made headlines this month involving a painting that might be by Vincent van Gogh.

In 2019, LMI Group International acquired the above painting from an anonymous antiques dealer, who bought the art at a garage sale in Minnesota for $50. LMI assembled a massive team of experts to authenticate what they believed to be a Van Gogh, and the result is a 456-page report that you can read here. At the time, the Van Gogh Museum quickly responded that they disagreed with the report’s findings. LMI Group’s chairman, president, and CEO Lawre…