Art, Commerce, and the Role of the Patron

Nowadays, we take for granted the concept of "art for art's sake." But for Renaissance artists, their work was often intimately tied up in the instructions and desires of their powerful patrons.

Last fall, when I decided to create The Crossroads Gazette, I knew early on that I wanted to call my paid subscribers “patrons.” The word “patron” possesses greater mystique than “subscriber,” and given that art is one of the main topics explored in this publication, it seemed a fitting decision. Thus, the Patron Podcast and the Crossroads patron community was born.

But what exactly is a patron? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word comes from the Latin patronus, a protector or defender of clients. (Harry Potter fans will no doubt recognize the patronus as a powerful protective spell.) The earliest known use of patron in Middle English comes from the Life & Martyrdom of Thomas Becket, written around 1300. The word possesses various meanings, including a supporter of the arts, a customer of a business, or the sponsor of an event. If you frequent a particular restaurant or café, you are a patron. If you’ve donated to a museum, you are a patron, too.

Patronage—that is, by wealthy individuals—played an essential role in the arts for centuries. William Shakespeare wrote Macbeth for his patron, King James I. Among Mozart’s patrons was none other than Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Beginning in the late 19th century, as industrialization allowed for mass-consumption of music, and a growing middle class led to the expansion of public museums and theaters, the influence of patrons began to fade. In came the advent of “art for art’s sake”—rather than creating a painting or writing a play to the specifications of a wealthy patron, artists created what they wished, and then had to find a buyer or an audience.

But for centuries, artists aimed to obtain patronage as a means of supporting their work. This was especially true for the visual artists of the Italian Renaissance, whose patrons ranged from wealthy merchants and bankers like Cosimo de’ Medici, to powerful church leaders and noble families, such as the Borgias and Sforzas.

If you recall from last week’s essay on the Mona Lisa, Leonardo’s most famous painting ended up in France because it was purchased by King Francis I. The Italian artist spent his final years in France because the king was in fact his patron. In exchange for becoming the “Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect of the King,” Leonardo received a pension and lodgings in the Château of Clos Lucé, where he resided for three years until his death in 1519.

The identity of the Mona Lisa, or La Jaconde, as she is known in France, has long been debated. Giorgio Vasari identified her as Lisa del Giocondo, an aristocrat from the Gherardini family of Florence and Tuscany; her husband was a successful merchant. However, Vasari never met Leonardo, nor did Vasari see the Mona Lisa in person. For hundreds of years, art historians debated the accuracy of Vasari’s statement.

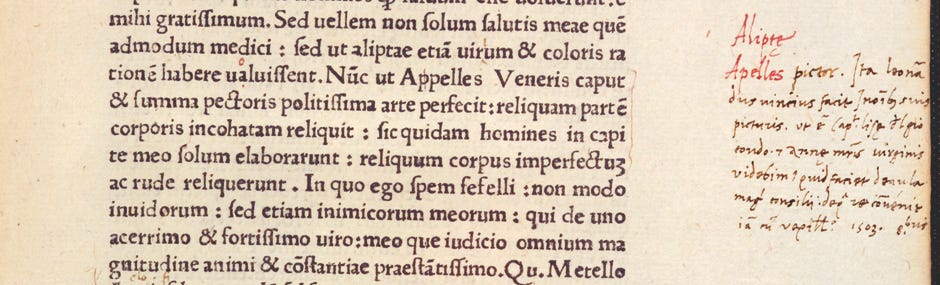

Things changed in 2005 when Dr. Armin Schlechter of the University of Heidelberg found a handwritten note by Agostino Vespucci (the secretary of Niccolò Machiavelli) in a 15th century publication of Cicero’s letters. Vespucci’s note is dated to October of 1503—around the time Leonardo began work on the Mona Lisa:

Apelles pictor. Ita Leonardus uincius facit in omnibus suis picturis, ut enim Caput lise del giocondo et anne matris uirginis. videbimus quid faciet de aula magni consilii, de qua re convenit iam cum vexillofero.

The painter Apelles. In this way Leonardo da Vinci makes it in all his paintings, for example the head of Lisa del Giocondo and of Anne, the mother of the Virgin. We will see what he is going to do with regard to the hall of the Great Council about which he has just agreed with the Gonfaloniere.

This discovery by Dr. Schlechter is the strongest evidence thus far that the Mona Lisa was Lisa del Giocondo, making it all the more fascinating that an affluent woman of a prominent family would allow Leonardo to experiment with new techniques to create his masterpiece. Unfortunately, very little is known about her life or the terms of the commission.

With regard to Italian commissions from the 1400s, several hundred contracts survive, though most are for paintings that have since been lost to time.* These contracts generally specified what the artist was asked to paint, how and when the patron would pay them, and the kinds of materials that should be used. The fifteenth century was a transitional period regarding the use of luxury materials in art—patrons still often wanted artists to use gold and expensive pigments like ultramarine as a means of displaying their wealth. But by the sixteenth century, the art market moved towards emphasizing the artist’s personal skill as evidence of a piece’s rarity, rather than the actual materials used to create it.

For example, when the Prior of the Spedale degli Innocenti in Florence commissioned Domenico Ghirlandaio to paint the Adoration of the Magi in 1488 (see above), he was particularly preoccupied with the quality of pigments used, as we can see in the language from their surviving contract:

…he must color the panel at his own expense with good colors and with powdered gold on such ornaments as demand it, with any other expense incurred on the same panel, and the blue must be ultramarine of the value about four flourins the ounce; and he must have made and delivered complete the said panel within thirty months from today; and he must receive as the price of the panel as here described (made at his, that is, the said Domenico’s expense throughout) 115 large florins if it seems to me, the abovesaid Fra Bernardo, that it is worth it…

As Michael Baxandall explores in Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy, the quality of pigments was a special concern for Fra Bernardo: “After gold and silver, ultramarine was the most expensive and difficult colour the painter used. There were cheap and dear grades and there were even cheaper substitutes, generally referred to as German blue.” The rich, ultramarine pigment in question was imported from the Levant and made from powdered lapis lazuli. Painters would soak the powder to “draw off the color,” with the first yield being the most vibrant and therefore the most expensive. This is why the Virgin Mary is typically cloaked in blue in medieval and Renaissance art—ultramarine was a precious pigment.

Some artists worked by commission, while others were paid a salary by a nobleman to work as their “full-time” painter. Leonardo da Vinci’s relationship with Francis I was exactly of this variety; it afforded the artist a stability that one would hope for towards the end of a long career. In either case, the right patron could catapult a painter to stardom, as the Medici family raised the profiles of Sandro Botticelli and Donatello. For the patron, art was a means of communicating wealth and power. As the fifteenth century progressed, and the quality of art became less about the materials used and more about the artist’s skill, the artist’s individual status rose in tandem. Great artists transformed from relatively-anonymous craftspeople to public figures.

Today, the idea of telling an artist what to paint seems downright odd. But for Leonardo da Vinci and his contemporaries, patronage was essential to financial stability, and securing a powerful patron was the goal of any person hoping to become a successful artist.

Are painters better off without patrons?

As a writer, my medium is accessible to a vast audience. Anyone can find a writer’s work online, and buying a novel from a book store is far cheaper than purchasing a painting. Books are valuable in their multiplicity, but the value of an artwork is tied up in its rarity. A masterpiece is “one-of-one.”

This poses enormous challenges for visual artists today—I would argue, far greater than the challenges that writers face. Would these artists benefit from a patronage system? Perhaps the closest example we have is that of fellowships, but it seems that the elites of our time value art far less than those of generations past. I can’t imagine having to make art to the specifications of a tech investor or a hedge fund manager. (Though even as I write that, I have to wonder if the Medicis would have been much different.)

And without the patronage system, what would artists like Botticelli and Leonardo have created? Would they have been more free in their creativity, or would they have been less well-known without their benefactors? After all, without patronage, the Mona Lisa wouldn’t exist.

As for my own patrons, my approach lies somewhere in the middle: I allow my curiosity to run wild in the Gazette, but I always leave the floor open to suggestions. My favorite podcast episode thus far (“Unicorns, From Ancient India to the Unicorn Tapestries”) came from a patron’s insightful comment.

Writing may be a solitary craft, but my work does not exist in a vacuum, and remaining open to others’ ideas and suggestions allows me to traverse new territories. Perhaps, even within the restrictions of their patrons’ expectations, the artists of the Renaissance had just enough room to innovate—and through this collaborative process, they revolutionized the arts for generations to come.

*For an excellent resource on the relationship between Renaissance artists and their patrons, I would recommend reading Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy by Michael Baxandall (Oxford University Press).

Recently on The Crossroads Gazette:

What Makes the “Mona Lisa” Special, and Why It's More Than a Simple Portrait - Last week, news emerged that the Louvre is considering moving Leonardo da Vinci's most famous painting to the basement in response to “public disappointment” and massive crowds. Read the full story here.

Standing On a Hill in My Mountain of Dreams - Thoughts on Romanticism, Led Zeppelin, and wandering with Caspar David Friedrich above a sea of fog. Read the full story here.

Exclusives for Crossroads patrons:

Patron Podcast: Beatrix Potter and the Children’s Publishing Revolution - Over 120 years have passed since Beatrix Potter published her first children’s book. Today, we’ll explore how one woman charmed millions of readers and became a titan of children’s publishing. Listen to the latest episode here.

Last week’s Crossroads Roundup: Major Neolithic Monuments Discovered, a Titanic Watch, and a Leonardo da Vinci Biopic - Our favorite stories on art, archaeology, folklore, and more from this past week. Read the full story here.

Very informative and interesting! I wonder, though, if you are not missing what for many artists has replaced the traditional patron, one that is all but invisible, or taken for granted, and that is the state, through endowments and arts grants, for groups and individuals. Here in Canada, at least, almost all 'fine art' painters and literary writers (poets etc) depend on government grants or are able to apply for them. It may be that we think it 'odd' to tell an artist what to paint, but it's not really the case that state 'patronage' is unconditional. An artist accepting funding from the government is is some fashion limited by what the government bodies tasked with doling our grants will accept. It's a largely unquestioned norm today to believe that governments should be in the business of supporting the 'arts', but I think a case can be made against it. Not making that case here myself, just offering a perspective that might be helpful.

I really enjoyed this, Nicole. It's fascinating to think of how art has changed over the years from patronage being pretty much the standard model for artists, to nowadays where personal creative freedom is much more prized. (And even the likes of Picasso or Degas generally refused to work to commissions!)

I guess in many ways, I guess it's a good thing that art is now seen as a much more individual/personal expression rather than something produced to specific requirements. But still, I definitely think the patron model had a lot of benefits too, as we can see beyond doubt by looking at the masterpieces that came out of the renaissance. So I do wish there would be more of a return to that in our modern world again.

Great work as ever!