Art and Culture in Edo Japan

Exploring the ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) of Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, and Hokusai—and the global impact of Edo culture.

In 1832, a 35-year-old Utagawa Hiroshige received the opportunity of a lifetime: an invitation to travel the Tōkaidō highway from Edo to Kyoto as a member of the Shogun’s envoy. The envoy would embark on a journey to the imperial court and present a gift of horses to the emperor.

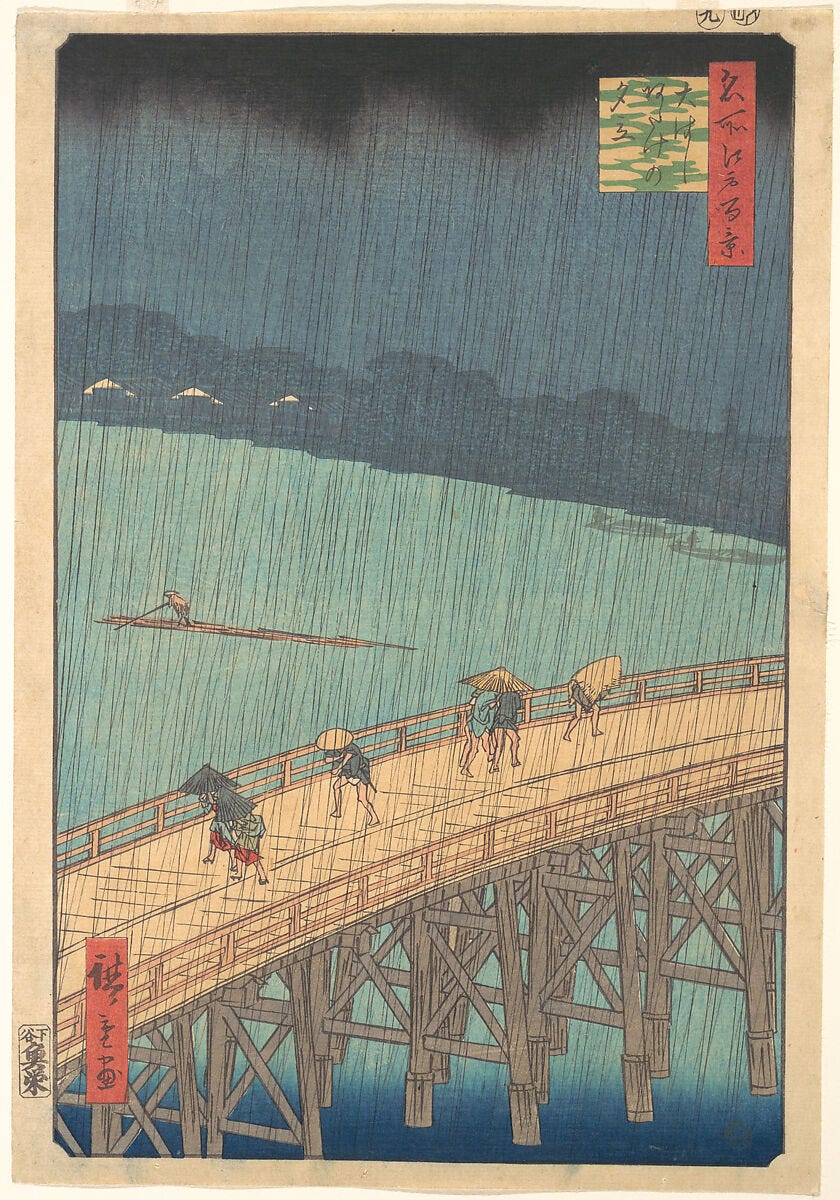

Travel was restricted in Edo Japan, and Hiroshige knew he had to make the most of the trip. At each stop, the artist captured images of busy markets, provincial towns, and rural landscapes. His evocative prints made ample use of new pigments that were hitting the market, such as Prussian blue.1 Furthermore, the bold hues and elevation of ordinary life present in his work would have a global impact; in particular, the Impressionists would find inspiration in his woodblock prints, and those of other Japanese artists. Today, the series born from his journey, called Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, offers viewers a window into Japanese life in the late Edo period—a place that was purposefully isolated from the rest of the world.

Over 200 years before Hiroshige traveled the Tōkaidō highway, Tokugawa Ieyasu vanquished his enemies at the Battle of Sekigahara in the year 1600. His victory ended roughly 150 years of civil war (known as the Sengoku period), and allowed him to establish the Tokugawa Shogunate. A series of fifteen Tokugawa shoguns would rule Japan from the new capital of Edo (modern day Tokyo), and the emperor would serve as a figurehead in his imperial palace in Kyoto… conveniently tucked away from the seat of actual power.

The Edo period lasted until 1868, and during this time, Japan experienced unprecedented levels of stability and economic prosperity. This peace, however, came at a price—the Shogunate imposed a strict policy of isolation, and the elite organized society into a feudal class system, with samurai at the top, followed by farmers, artisans, and merchants. Feudal peasants, as in medieval Europe, had limited freedom of movement. Travel beyond one’s community required special permission, and because there were no wars in which the samurai could fight, the warrior class occupied administrative roles.2

Therefore, Hiroshige’s art helped viewers get to know parts of their country that they may not otherwise have had a chance to see. His prints were incredibly successful; thanks to this demand, he followed Fifty-three Stations with Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Highway and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Edo-era woodblock prints are known as ukiyo-e. The word “ukiyo,” or “floating world,” was used to describe the urban culture of Edo under the Shogunate. The stability of Tokugawa rule meant that cities grew rapidly, and entertainment districts featuring teahouses, kabuki theaters, and brothels grew along with them.3 Artists captured this “floating world” via woodblock prints, which allowed for the dissemination of their work at more affordable prices. Even though the Japanese government maintained isolationist policies, small amounts of trade were permitted, and woodblock prints by European artists made their way into the country. These prints served as a source of cross-cultural exchange.

Artistic schools developed to mentor ukiyo-e artists, such as the Utagawa School. Founded by Utagawa Toyoharu in the late 1700s, the Utagawa School became the largest ukiyo-e school in Edo Japan. Members adopted the Utagawa name as part of their own (hence, Andō Tokutarō became Utagawa Hiroshige). Toyoharu adopted the use of single-point perspective that he learned from European prints and pioneered the technique for Japanese artists.4

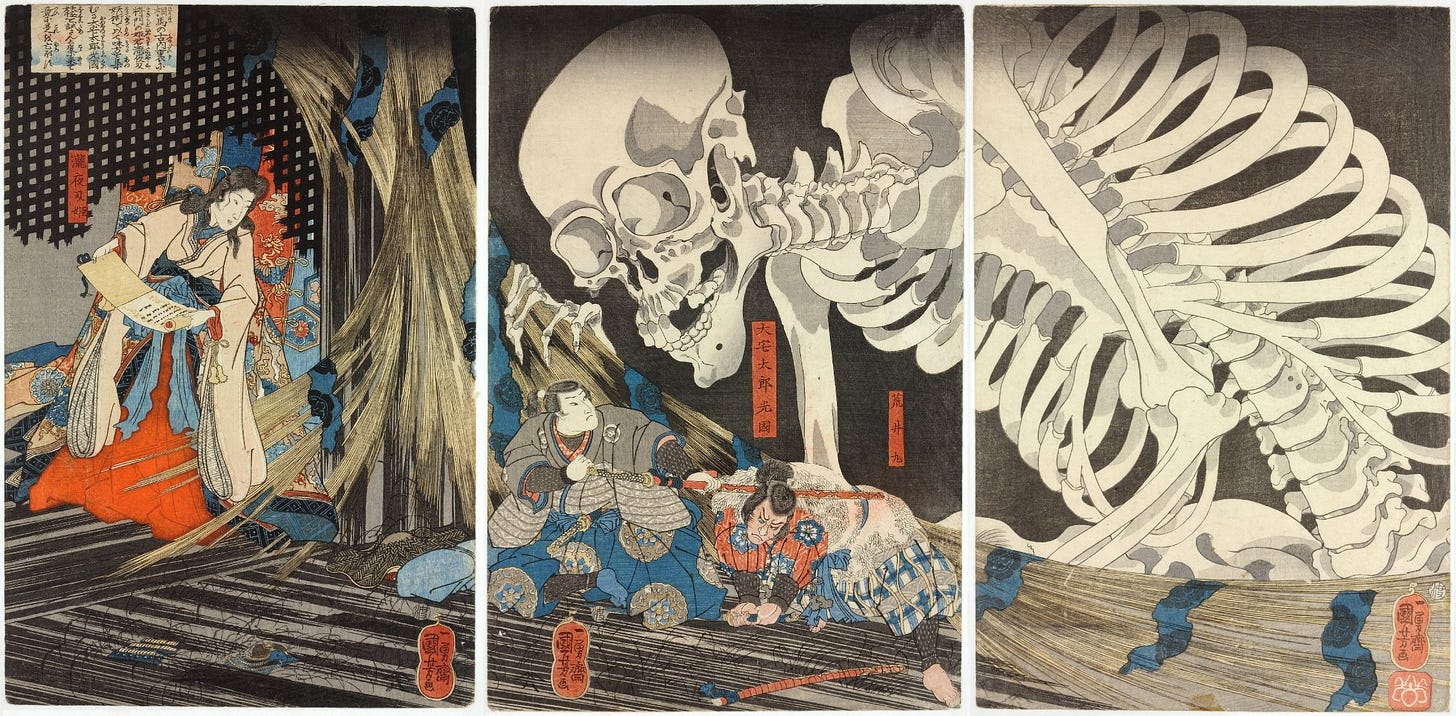

Utagawa artists had the leeway to explore different genres and subject matter. While Hiroshige would specialize in landscapes, another prominent ukiyo-e artist, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, favored “musha-e” or warrior prints. Kuniyoshi produced magnificent triptychs such as Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre (1844), which was inspired by a kabuki play based on the life of 10th-century warrior Mitsukuni.5

Kuniyoshi loved capturing theatrical scenes, especially those featuring samurai or mythical beings. Kabuki actors also provided inspiration for his art, and among his many images of cats (Kuniyoshi was definitely a cat person), some include cats dressed in kabuki costumes.

But the most famous Edo-era print has to be The Great Wave (1830-33) by Hokusai, part of the artist’s series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. Hokusai was an eccentric person with a varied career: he changed his name over thirty times (which is perhaps why he is known monomously), produced over 30,000 designs, and moved ninety times during his life.6 The Great Wave, a monument to human vulnerability in the face of nature’s power, influenced Japanese artists like Hiroshige as well as artists abroad. The print became a global sensation, and to this day, it is one of the most easily recognizable works of art in the world.

If Japan remained in isolation, how did the Impressionists gain access to Hokusai’s work? In 1852, U.S. president Millard Fillmore chose Commodore Matthew Perry to embark on what is now known as the Perry Expedition. The goal? Forcing Japan to end its policy of isolationism. Perry’s “gunboat diplomacy” (intimidation) worked, and the forced opening of Japan launched a cascade of Western influence that would eventually lead to internal conflict in Japan and the collapse of the Shogunate. The 1868 coup d’état by a coalition of samurai ushered in the Meiji era, which restored power to the emperor and ended feudalism in Japan. The imperial family moved to Edo (renamed Tokyo), and one can see the influence of Western fashion and design in woodblock prints inspired by the event (see below).7

While the Meiji era still saw the production of ukiyo-e, enthusiasm for Western fashion, architecture, and technology spread through the country. The world captured by Hiroshige and Hokusai soon faded away.

I say that while noting the complexities of the moment—I doubt that feudal peasants mourned the collapse of Edo hierarchies that kept them firmly at the bottom rung of society. But the Meiji government, in its urgency to adopt all-things-European, oversaw enormous destruction of cultural heritage sites, along with the imposition of Western clothing and hairstyles. In the pursuit of industrialization, aspects of heritage that made the Edo era special were lost.

As the Japanese imported Western styles, European artists revered the likes of Hokusai and enthusiastically adopted Japanese techniques and color schemes. Japanese culture, in that sense, played a key role in the Western artistic revolutions of the late 19th century, just as Japanese artists from Takashi Murakami to Yayoi Kusama influence art, fashion, and design today.

It’s tempting to think of Edo ukiyo-e as embodying a lost world, floating ever away from us, as the boaters in The Great Wave succumb to the sea. But when I view the works of Hokusai alongside the legions of artists he would inspire, I am reminded that the flair and vibrancy of the Edo masters caused a global ripple effect—and we remain connected, looking back from the outer ring.

Related essays from The Crossroads Gazette:

Capturing the Beauty and Terror of Winter - How the winter months inspired artists across regions and time periods, from Pieter Bruegel the Elder to Utagawa Hiroshige. Read the full story here.

Dragons of the East and West - Dragons, both benevolent and wicked, appear in folklore, literature, and art all across the globe. On the origin of dragons, and the myths and legends they inspired. Read the full story here.

“Ando Hiroshige” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 339.

“Japanese Art (17th and 18th Centuries)” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 285.

“Utagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print, 1770–1900,” Brooklyn Museum, March 21, 2008, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions/665.

“Utagawa,” Brooklyn Museum.

“Utagawa Kuniyoshi” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 339.

“Katsushika Hokusai” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 338.

“Japanese Art (19th Century)” in Art: The Definitive Visual History, ed. Andrew Graham Dixon (New York: DK, 2018), 338.

As always a wonderful exposition! Reminded me of listening to the In Our Time radio on the same subject. Have you thought about recording your articles? I would shy away from such a task myself, but then I write fiction.

All about the hot spring baths at every stop!